Tribal art: old market, new perspectives ?

Rather marked by its stability, the tribal art market seems to be approaching a period of loading and change. So as to question its foundations ? A snapshot of a market.

The “tribal art” market (commonly called by its reviewers to bring together African, Oceania and American classical arts) is a small appendix to the international art market. Alongside its annual $60 billion and its highest records, it does not weigh much, it is true, and appears more like a niche market, a specialty for passionate collectors. In 2017, it can be estimated from the figures in the specialised Artkhade database (all the figures quoted in the article come from the same source that aggregates the results of auction houses) that the world turnover of the auction sector slightly exceeded €80 million, resuming growth after a slight slowdown between 2016 and 2015 (respectively for the years 65 and 70 million euros). It should be noted that in this market, as in others, we only have the results of auction house sales – those of dealers do not have to be made public.

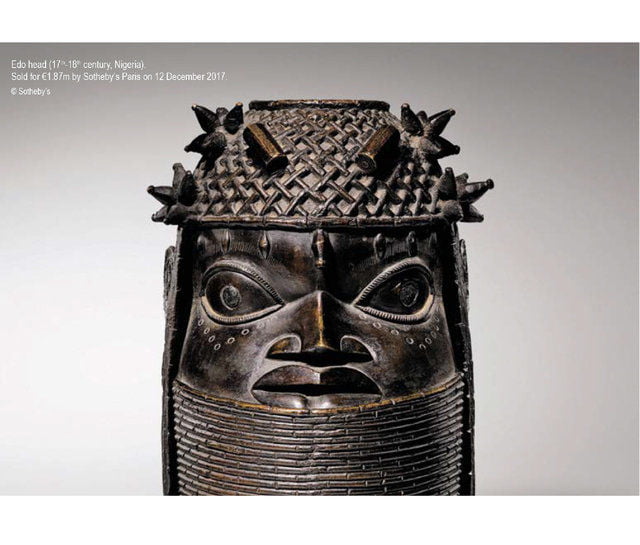

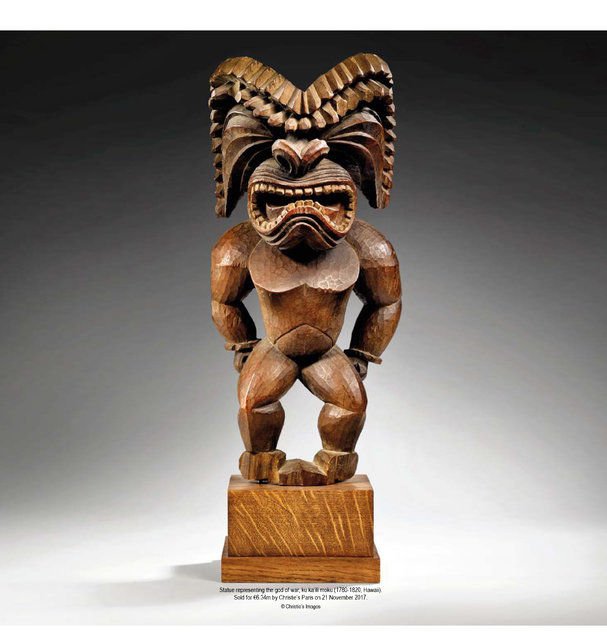

In 2017, as usual, the lion’s share was split between African (€38.8 million) and Oceania (€27 million) artworks, and France is at the top of the class – it represents nearly 65% of the market. Regarding the record for tribal arts, it was auctioned in 2014. It was a female Sénoufo statue (Ivory Coast or Burkina Faso), gone for $12 million (fees included). This is a far cry from the $450 million achieved by Leonardo da Vinci, or the $110 million of a Basquiat, which was auctioned at Sotheby’s in May 2017. “Why should masterpieces of African art sell for 10 to 100 times less than some of the paintings of the pioneers of modern art who recognized in them the proof of an exceptional mastery of statuary, and from which they drew inspiration? “, asks Jacques Germain, a specialist in the ancient art of Black Africa.

However, for the past twenty years, both the figures from public sales and the feedback from merchants and experts have shown that the market is healthy, growing and fairly stable in its practices. In addition, the very dynamic sales of the last few months confirmed a year 2018 at the high tempo.

Most recently, Sotheby’s was a great success with the dispersion of the Elizabeth Pryce collection in Paris. All the lots have been sold, what the Anglo-Saxons call a “White glove sale”. In total, one million euros and twice the low estimate expected before sale. The session record, at €225,000, was awarded to a biwat flute cap (Papua New Guinea). “After the Murray Frum collection, Sotheby’s was pleased to pay tribute to another great figure who worked for more than 50 years in support of Oceanic art, Elizabeth Pryce,” proudly announces Alexis Maggiar, European Director for Arts in Africa and Oceania. Like the surrealist artists, she was fascinated by the ability of Oceania’s works of art to arouse emotion.

“Why should masterpieces of African art sell for 10 to 100 times less than some of the paintings of the pioneers of modern art who recognized in them the proof of an exceptional mastery of statuary, and from which they drew inspiration? “, asks Jacques Germain

The “Vente Frum” to which the auctioneer refers was one of the biggest successes of his company. It was 2014, and Sotheby’s not only managed to disperse this prestigious collection, but also that of Myron Kunin – from whom the Sénoufo statue mentioned above came. Together, they represented a turnover of €45.4 million. An impressive figure, never seen before, for this small market. This sale is one of those famous large collections that were auctioned off, as was the “Vérité” collection, which was scattered at the same time as the opening of Quai Branly in 2006, which generated €44 million with the fees. A memory that everyone has kept in the market.

Inertia and ruptures

On 30 October 2018, Christie’s Paris sold 30 works from the Palais Stoclet, the megalo architectural work of a leading entrepreneur of the early 20th century, Adolphe Soclet, who also collected African art. The sale of the objects generated almost €1.4 million (with fees), thanks to the excellent result achieved by a Yaka headrest (Democratic Republic of Congo) sold for €1.2 million. Earlier in the year, the Durand-Dessert collection was rather disappointing in Paris in June 2018, even if a majestic Mbembe figure (Nigeria) left for €1.9 million. In short, signals that appear to be positive.

“(…)The price increase only concerns the most lucrative, high-profile segments of the market.

However, behind all these good results and profitable sales, there are two phenomena behind them. First, the price increase only concerns the most lucrative, high-profile segments of the market. It rewards what are called “museum quality pieces” (an expression that resembles a marketing label rather than an historical observation of art). In fact, the median price of an African art object fell from €5,500 in 2012 to below €1,000 in 2017 – a historically low level.

“Many of our customers are people who travel all the time. For them, it is therefore easier to choose pieces on online auctions than to move around in real galleries. » Pierre MOOS

The market is becoming polarized, therefore, and the trend is more noticeable at auctions. “This soaring price is largely due to the fact that most of the “large objects” are known, listed and especially coveted by members of the “tribal” community and for this reason, at public sales, their high quality and irreproachable provenance make them trophies that are increasingly popular with the connoisseurs,” notes Jacques Germain. For his part, Pierre Moos, who organizes the “Parcours des mondes” exhibition every September in Saint-Germain, notes that “at the level of merchants, there is a drop in activity throughout the world, which is due to competition from major auction houses that cap the top of the basket but also and especially that from the Internet. Many of our customers are people who travel all the time. For them, it is therefore easier to choose pieces on online auctions than to move around in real galleries. »

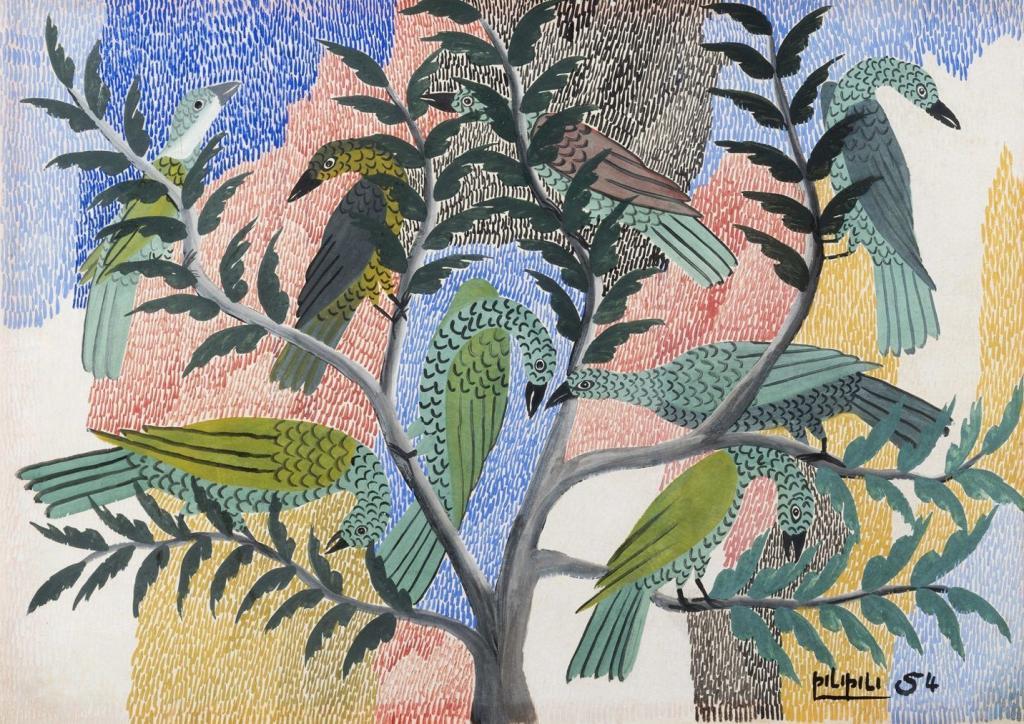

In short, things are changing. And if so many collections have been scattered lately, it’s for a good reason. Those established since the 1950-60s are coming to an end. Collectors pass the baton, some disappear and sometimes their children do not always wish to follow up on their parents’ collections, and so give them up at auction. We were currently witnessing a change of generation. This also gives rise to the arrival of new heads. In recent years, Lucas Ratton (son of a great merchant himself), Indian Heritage, Alexis Renard, Nicolas Rolland and Charles-Wesley Hourdé (who opened his gallery after five years as director of the Christie’s Paris department) have settled in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, between the Seine street and the Beaux Arts street.

An old market

Moreover, during the last edition of the “Parcours des mondes”, the latter two organized an exhibition that did not go unnoticed. It was a tribute to a mythical exhibition held in 1930 at the Pigalle Gallery. Among the 400 pieces of this event, which some historians consider to be the birth certificate of the “primitive” or “nigger” art market, it was said then, they have gathered about twenty of them. “The Pigalle exhibition alone sums up all the symbolic and economic issues related to the recognition of the early arts in France between the two world wars”. This event comes at a key time in the formation of the market. At the end of the 1920s and during the 1930s, specialized vacations dedicated to the arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas multiplied at the Drouot Hôtel. Going beyond the cenacle of the avant-garde artists who initiated the passion for “black” art at the beginning of the century, the circle of amateurs is widening. We are seeing the emergence of new collectors from a variety of backgrounds. Merchants, experts and various specialists multiplied, as did scholarly works dealing with primitive arts.

All this contributes to structuring the market and increasing the price of objects, the most sought-after ones being traded at very high prices from that time on. The exhibition at Galerie Pigalle truly embodies this new era. Its organizers (Charles Ratton, Tristan Tzara and Pierre Loeb) solicited avant-garde artists (Picasso, Braque, Matisse, Miro, etc.), specialized dealers (Guillaume, Ascher, Moris, Hein, etc.) and the greatest collectors of the time (de Miré, Chauvet, Tual, etc.).

The works from Africa and Oceania that were presented there were for many exceptional. The exhibition, through its formidable media and popular response, thus contributed to the idea among the general public that these statues and masks were works of art in their own right and that in this respect they had a value that many people then ignored. “It is amusing to see the analogies of a market such as the one described by Nicolas Rolland and Charles-Wesley Hourdé with what is currently happening.

Indeed, the resilience of the tribal art market is strong, and its small size protects it (still?) from financial predation, to the benefit of the passion of its actors. Will the current turmoil, this change of generation, the development of online platforms and market polarisation change this age-old structure? We can still afford to doubt it…