Culture as resistance: Sifiso Khanyile on documentation and archiving

T

he events of June 16, 1976 are well documented in South Africa —on that fateful morning a group of students across South Africa led demonstrations against the Bantu Education, specifically the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction. Hundreds of school kids were shot and killed by the apartheid government in what would later be known as “the 1976 Uprising” or the “Soweto Uprising”.

Most documentation of this historical event is deficient in that a) it only focuses on Soweto while excluding and erasing other locations where protests took place and b) it documents the Uprising as a singular specific moment that happened very quickly. The reality is that demonstrations were widespread and took place across the entire country and students had in fact been organising and raising consciousness months before this event.

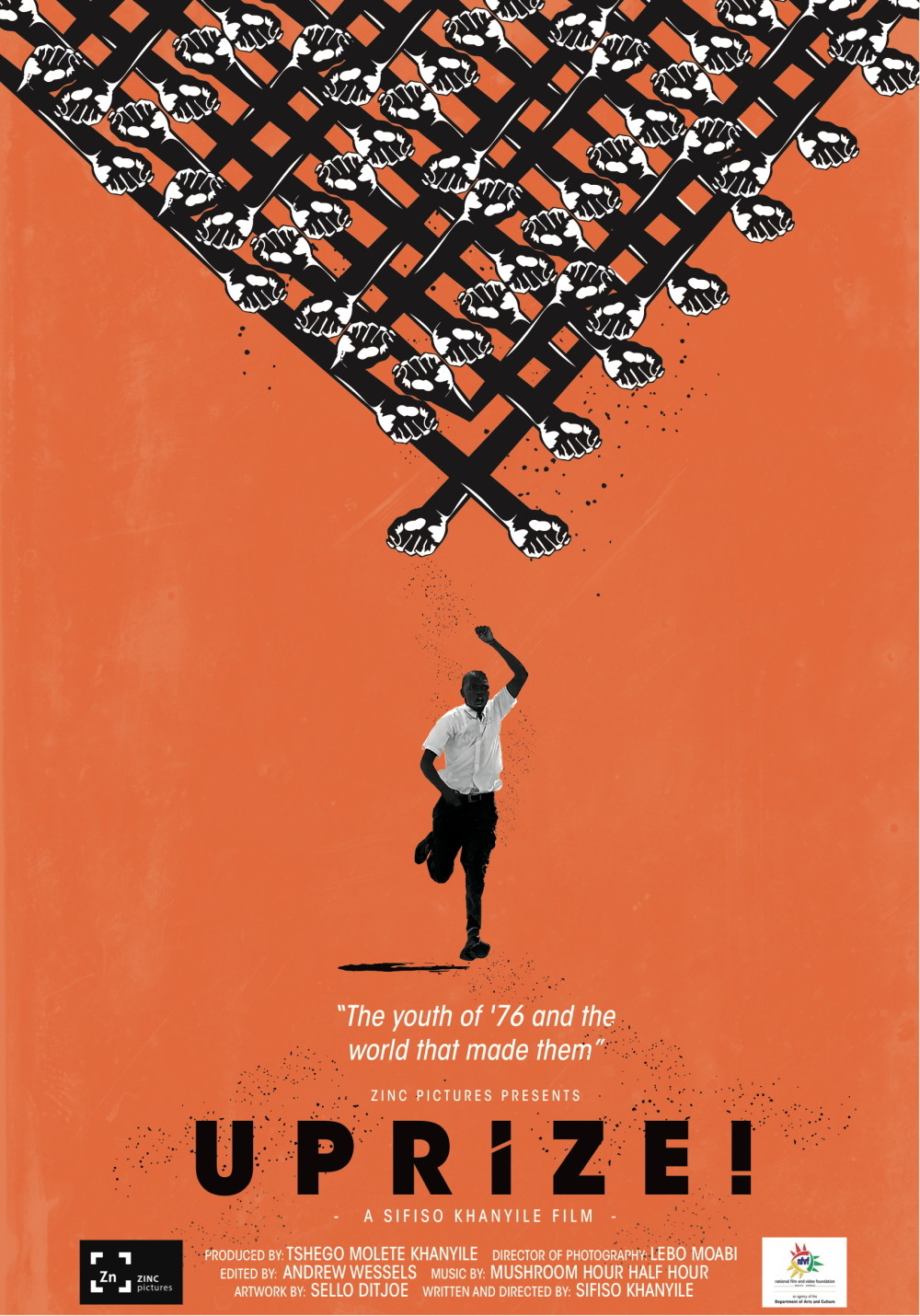

In 2017, filmmaker Sifiso Khanyile released the documentary; Uprize!—an unmasking of how South African students embarked on cultural resistance to challenge an unjust and oppressive apartheid government. Two years after its release, I was quite interested in reflecting on the process of making the documentary, particularly in relation to archiving and documentation; how do we record critical historical events and how can these documents and records later be used? Who owns the archive and to what extent do they possess the power of translation and re-interpretation?

Below is my interview with the filmmaker.

Nkgopoleng Moloi (NM): In making Uprize!, what portion of the footage was archival material?

Sifiso Khanyile (SK): The archival footage takes up a large part of the documentary. I’d say about 35% of total duration of the film. Not as much as intended initially as licensing fees for archives became a huge hurdle for us in our selection process, we had to curb our excitement and work with what we could afford.

NM: What was the process of getting to that material?

SK: I had to brief my archive researcher on the sort of images I was looking for and the feeling I wanted them to invoke while keeping in mind the politics of the image, i.e. how these images portray their subjects, are they triumphant or defeated, organised or disorderly, etc. We cast a wide net and through the process of elimination we made our choice —taking into account costs, accessibility and the extent to which these images had been previously distributed and seen (we didn’t want to use images audiences were desensitised to).

NM: Which organisations did you engage with to gain access to that imagery?

SK: Villon Films, ITN Source, SABC Archives, AP Archives, Independent Media, Chris Austin, Times Media, UCT Press, Reuters, Mnet —quite a few. I’ve been working with archives from about 2012 and therefore quite aware of photo and video costs. Initially we planned on using more archival footage but had to concede that we could not afford it all. The strategy shifted towards sourcing generic images with local sources [mainly the South African Broadcasting Corporation (SABC) ]. We also had access to some rare/ exclusive record of historical moments which we used economically.

NM: How did you know what material you were looking for? Was this a process of mapping out historical events and finding what related to that or more a process of looking through records that exist & deciding what seems useful?

SK: I have been researching and writing on different anti-apartheid cultural resistance movements for a while. In 2012 I produced Prisoner 46764: The Untold Legacy of Andrew Mlangeni —this was a documentary on struggle stalwart Andrew Mlangeni. For that documentary, we worked with a lot of political history archives, during this time I was also a news producer for an American Network; sourcing archival footage related to Nelson Mandela, apartheid and the early 90s political transition.

NM:Is there a discrepancy in terms of access between what is documented across different mediums; for instance, are images easier to come by compared to formal documents, certificates, deeds, etc?

SK: I think it all depends on what you’re looking for and what story you are working on. There may be tons of court papers for one story and no images, and vice versa.

We have a complicated past and in some instances records were in fact destroyed or damaged —sometimes this erasure becomes the story. This also speaks to the materiality of the archive, what was it shot/filmed on and how it was preserved and if there were any restorations done. Another key consideration is; who had the resources as the events were unfolding? For instance, SABC TV was only introduced un 1975, this means not much film and video newsreel archive exist before this time. Most of our video archives for periods before 1975 are sitting outside of the country.

NM: Were there specific moments that shocked you when you reconciled your own memories of events vs what you found out through research (specifically around 1976)?

SK: I was not born yet when ’76 happened therefore I draw from what is public ( how the story has been documented and shaped). I discovered that history is not static, there is always room to present a different view. Objects that might have served a specific purposes might go obsolete, leaving a lot of space for alternative narratives. I was interested in the finer details of the ’76 story, the specific roles that shaped the events.

NM: Which institutions are doing a good job un documenting history as it happens?

SK: The news networks and agencies are great for the TV and video documentary space, both local and international. I’ve come across some great personal archives from filmmaker and photographer friends who constantly want to capture the zeitgeist of this country without necessarily making this an assignment. Writers are what connect me to most stories in the first place and their role is pivotal in how we engage with history.

NM: What practices do you have for documenting your own personal history? Why does this matter?

SK: I’ve been thinking more about this since the birth of my son. A profound sense of mortality confronted me. I had questions about the kind of legacy I want to leave for him. I remember gathering and storing images from my travels, talks, my writings, TV and radio interview clips, etc. I found videos I had shot at family events over a decade ago and was reminded how my journey in film started. For the first time in a while I felt like the lens was turning away from what I want to capture as a documentary filmmaker and towards me and my story.

I felt an urge create more work —to write and document my story, for posterity, so that my son can have a better understanding of who I am when he can no longer have access to me.

NM: What are your thoughts on dramatisation in historical documentaries —were filmmakers re-enact scenes where they do not have actual imagery of the events?

SK: There are stories that have to survive, one way or another. There are individuals whose impact on society needs to be celebrated — Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe is one of them. It is a great tragedy that a lot of his records were destroyed. Filmmakers and storytellers have to find ways of keeping his memory alive. Film is a visual medium that mostly relies on audience engagement for its success. This is one of the instances where re-enactments become necessary, not just for dramatic value, but to capture the spirit of a person or event.

NM: What is the starting point in approaching a historical documentaries? For instance if I wanted to think through Marikana Massacre or Fees Must Fall Movement …where would I begin?

SK: Start by questioning your own intentions, your perspective, your relationship or connection to the stories or people whose lives you want to document. What are the burning issues? What are you telling us that we don’t know? The film can also be an exploration or voyage of discovery for a different generation. Start by conducting a lot of research; writing an outline for your idea and constantly refining your story.Look for funding but also see what you can do while waiting for funds. Plan everything, map out how you want to approach the film’s aesthetics, your position in the film, who you want to speak to and how you’re going to gain access to those people. Reach out to people you want to see in the film to gauge their interest and to test the strength of the idea. The idea needs to be clear in your head and then on paper, before you consider filming anything.