Shot in the Dark —Billy Monk and the Cape Town underworld

Billy Monk was buried at sea on a thick grey Cape Town winter’s day. The sort of day that looks as if it needs to clear its throat. The sea had that chip-chop movement of a child’s drawing; up –down,plip-plop, sick-sick.The movement of the boat was relentless and some people said it was Billy Monk’s last revenge. Lin Sampson

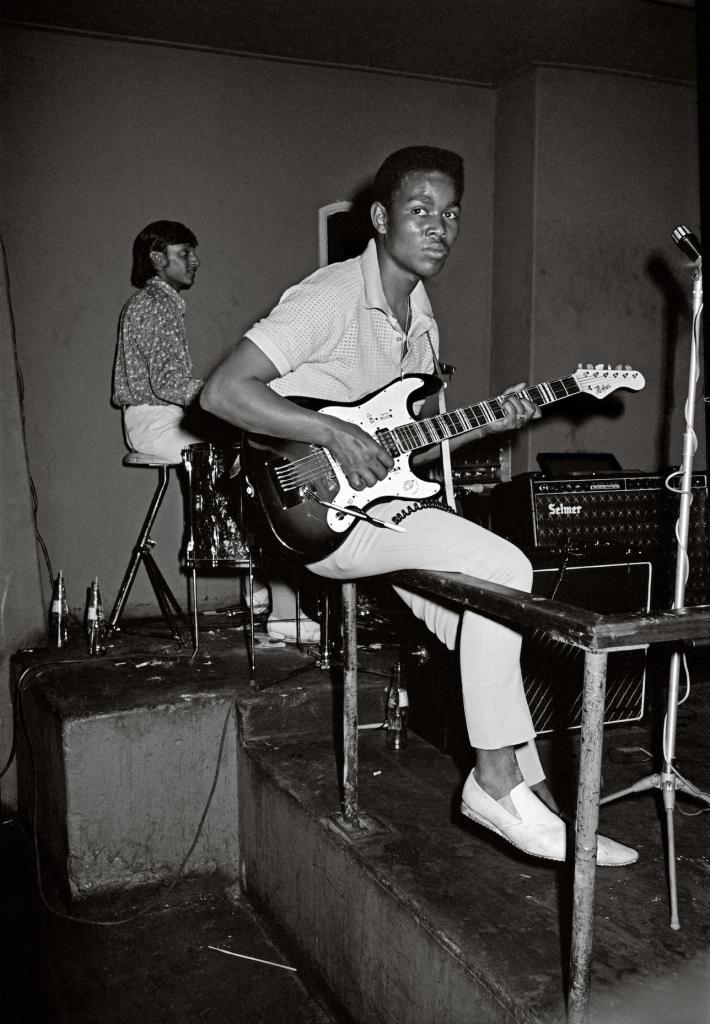

Billy Monk was a photographer working in the 1960s in Cape Town, but much more than that he was a vagabond; transient and spry—moving from job to job while also capturing the Cape Town underworld. In 1982 an exhibition of Monk’s work was presented at The Market Gallery in Johannesburg…Monk tragically died before seeing it. In engaging with Monk’s work and trying to decipher it, I reached out to Craig Cameron-Mackintosh, one of the custodians to the Billy Monk Collection (a small but important archive of Monk’s work). We spoke about Monk’s life, his work and legacy.

NM: Can you tell us a bit about Billy’s childhood; his early family life, where he grew up etc?

CC-M: Not much is known about Billy Monk’s early life. In my interviews with his son, David Monk, it’s apparent that Billy didn’t speak about it much either. David got the impression that his father had a tough upbringing. Originally from Johannesburg, Billy resorted to burglary to survive, eventually spending two years in prison after a botched heist at the OK Bazaars on Eloff Street. Apparently in the heat of the chase, Billy and his accomplices wrestled the security guard to the ground and Billy grabbed his gun. He refused to shoot though, foiling any chances of escape.

NM: On the 1982 show —It has been thirty seven years since that show at the Market Gallery; what would you say the images are revealing now that they were not revealing three decades ago?

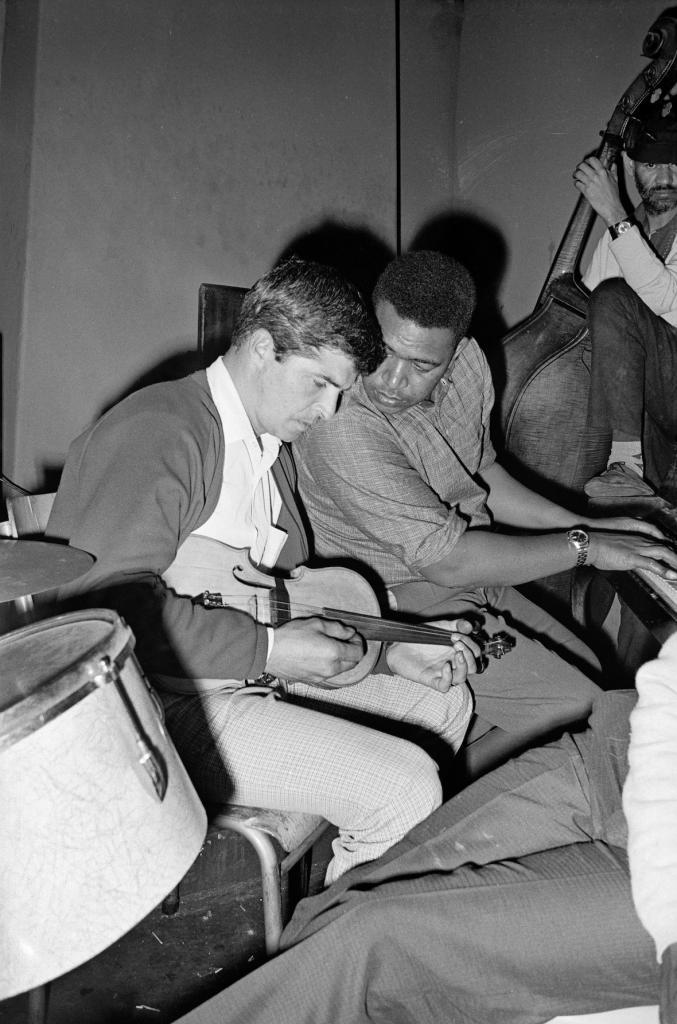

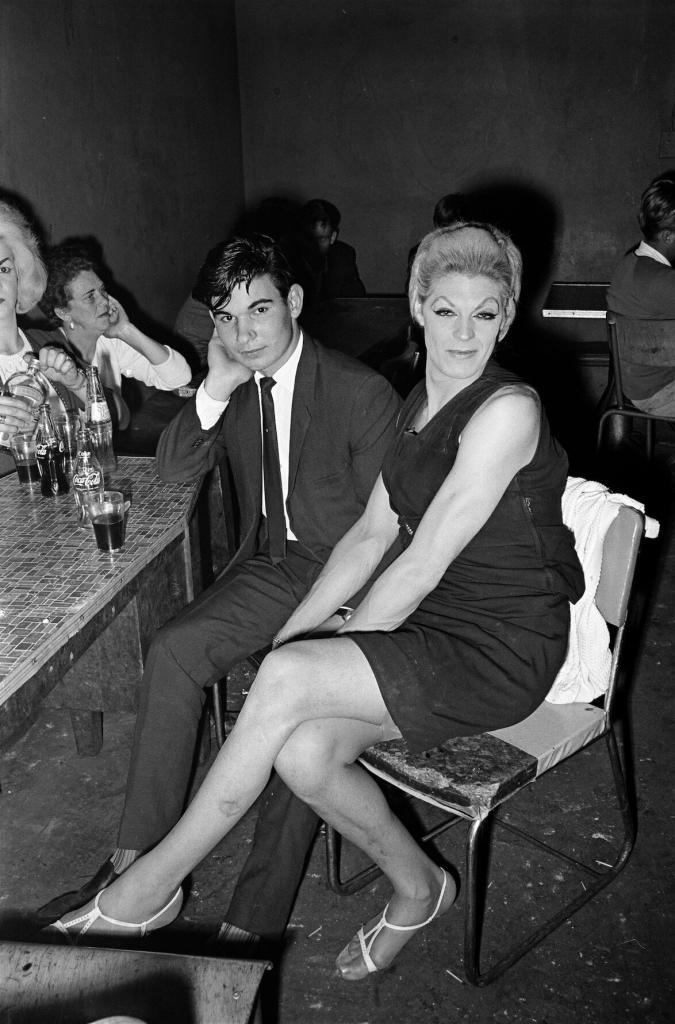

CC-M: Good art, and cinema, reflects the current times. Billy Monk captured a cross-section of society that was completely against the laws and acts that divided our country at the time. But of course capturing it is one thing, exhibiting it is another and unfortunately this was not an option for Billy in the late 1960s. He had even been in trouble with the law due to the fact that his common-law wife, Jeanette, was classified as coloured.

The 1982 exhibition – Nagklub – was curated by Jac de Villiers and Andrew Meintjes and although they had access to the same archive as I do, it should be remembered that this was very much still in the grips of apartheid. But in my conversations with Jac, he explained that the series of Billy Monk images that they released followed the sequence of a typical night at the club and was not attempting to make any other kind of statement. As the narrative flows, first of all the audience is exposed to the sense of light-hearted fun in the club. As the evening progresses, the selected photographs reflect a darker mood and a “sharing of secrets”. Finally, the narrative lays bare the scandal and the shame.

Relooking at the images now with different viewfinders in a democratic South Africa, I would say that they reveal scenes of hope. They show that even in the worst of times, joy, fun and inclusion existed and can still.

NM: What was Billy’s own attitude towards his photographs —did he see them as work? Given what we know about the man, what do we imagine would be his attitude now?

CC-M: Billy Monk definitely had the ambition of becoming an acclaimed photographer. He understood that the images he took of smiling sailors and nightclub patrons were ‘happy snaps’, which were sold back to them as souvenirs but that his artistic shots were something separate. He had a sharp eye and spotted fleeting moments and personal dramas. Whether posed or taken without his subjects knowing, Billy clearly had a natural gift for framing and telling a story through his images. He often retold the accounts of his nights at the club to his housemate, Paul Gordon, thrilled by the scenes he had snapped.

Had Billy not been tragically killed in 1982, I think he would be pleased at the impact that his work has had on anyone who’s seen the collection. But knowing a little bit about his personality and the way he moved through like as a “factotum”, as art critic Ashraf Jamal described to me in an interview, I can’t imagine Billy embedding himself in the art world specifically. I’m sure he would’ve continued to photograph the world around him so beautifully though.

NM: On the documentary; Billy Monk – Shot in the Dark —how was this documentary initiated?

CC-M: I have a background in filmmaking and so it was a natural decision to create a short film about Billy Monk and the underground world that he captured. The idea was that the video could accompany any future photographic exhibitions but soon grew in scope when I uncovered the layers in this story and learned how interesting the man was. Even at 37 minutes in length, the documentary leaves questions with the audience and makes you want to learn more.

NM: I want to speak to the title of the documentary; “Billy Monk – Shot in the Dark” It is quite alluring, like the man himself….can you speak to this title?

CC-M: One of my film’s co-producers, Cait Pansegrouw, suggested the title and I felt it spoke a lot about the man and his story. A double, or even triple meaning; referring firstly to these graphic photographs of dark nightclub corners, lit up with stark flash, revealing so much about this underground world. Also of the fateful night Billy was shot with a .22. Lastly, it hints at the sheer chance of Billy Monk’s images even making it to the light of day after having spent over a decade inside a box.

My aim with the film was to reveal a little bit more about the man and this subculture that he was a part of, while maintaining the allure and legend around him. Some questions are raised but not necessarily answered in full.

NM:What plans do you have for the documentary, in terms of where it will be screened, when and why?

CC-M: I’m pleased that the world premiere will take place at the Encounters South African International Documentary Festival in Cape Town and Johannesburg from 6th – 16th of June. I look forward to showing this Capetonian story to a local audience because so many South Africans were not aware that this subculture existed.

After that, I hope to screen it at international film festivals around the world and have begun the submission process. It’s a universal story that’s relatable to all audiences. I also love that it’s a refreshing take on this part of South Africa’s history. Even in the darkest times, there are always pockets of society that don’t agree with the powers in charge and find (or create) spaces to dance, drink and just have fun. Billy Monk too, is the ultimate hero of a story like this. So totally against the racist regime of the time and living a life that went against it completely. Luckily for us, he was documenting this for us all to enjoy, five decades later.

NM: I imagine the process of going through the collection has made you reflect more on the practice of photography – I’d be interested to find out your thoughts on Susan Sontag’s view of photography as an aggression “Essentially the camera makes everyone a tourist in other people’s reality, and eventually in one’s own.” — Susan Sontag

CC-M: Susan Sontag’s quote really makes one think about the effects of photography, especially when the photographer allows the viewer to safely dip into a world as different as 1960s dockside Cape Town. The first task as custodian of Billy Monk’s archive was to digitise the entire catalogue for ease of reference. It took a few days to view all the photographs and by the time I had seen each and every image I felt I had been changed. I felt I had lived, if only briefly and through someone else’s eyes, in this underground world. However, the black and white gave it a certain distance and a degree of separation. Much like a brief vacation – enjoying the sights from a superficial level but not necessarily understanding the culture.

But what’s so evident in Billy Monk’s archive is his sensitivity to the people he photographed. He wasn’t commenting or passing judgement on his ‘subjects’, nor was he acting as some sort of voyeur. Instead, he was simply documenting the world he was a part of, in an artistic way. He was very much a part of this scene, embracing and living all aspects of it. This is apparent when looking at the archive and realising that none of the characters are blocking their faces or resisting being photographed. In fact they’re playing up to Billy and his camera. And so rather than being an aggressive tool to unwilling subjects, Billy’s camera was a welcome part of the scene.

The effect on the contemporary viewer may be of shock or curiosity as we look into an unknown world, but at least in Billy Monk’s case, there’s a sense of authenticity there. I also love that although these images were taken exactly 50 years ago and we as an audience watch with fascination at this different time in history, there’s a certain sense of familiarity too. The way that trends return (they called it ‘stovepipe slacks’, we call it ‘slim fit’, for example) and the recognizable scenes of people drinking, dancing, passing out. We’ve all been there.

NM: Can you take us through the process of sorting and cataloguing this collection; how long did it take and what did the exercise entail?

CC-M: As mentioned, the first task was to digitise each photograph for ease of reference and for posterity. Luckily Billy meticulously labelled and filed his negatives and each spool was accompanied with its corresponding contact sheet. The negatives are in great condition because of the care he took with them, despite them being 50 years old. They’re currently being kept in a temperature controlled storage vault.

In terms of putting together a new collection of previously unseen photographs that was unveiled at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair earlier this year, this involved a massive exercise in editing and creating larger pools of great images. Starting with separating the ‘happy snaps’ from the artistic shots. Billy’s hand written notes and marks on the contact sheets helped me in deciding which images he liked but of course a lot of subjectivity goes into the decision making too. I looked at photography standards like composition, focus, exposure and other technical merits but also whether the image told a story beyond what we see in the frame or simply whether the image makes the viewer feel something or even just smile.

NM: In your view, what is Billy Monk’s legacy?

CC-M: Billy Monk has given us a rare glimpse into a secret world. Beautifully documenting a place that would have been left largely unknown had he not. His legacy is an honest portrayal of a small yet fascinating Cape Town subculture, demonstrating what Ashraf Jamal calls “love in a loveless time”. The audience has the pleasure of viewing this world through his viewfinder, as close as you can get to his point of view.

***Director Statement: Billy Monk – Shot in the Dark is a celebration of a little-known slice of South Africa’s history. Through Billy Monk’s photographs and his own tragic story, I aim to shine a light on the many marginalised communities that existed in Cape Town in the late ’60s. This is a film about Billy Monk but also about inclusion, joy and just having a good time, despite the situation.