The silenced past is confronted and histories converge with author Novuyo Rosa Tshuma

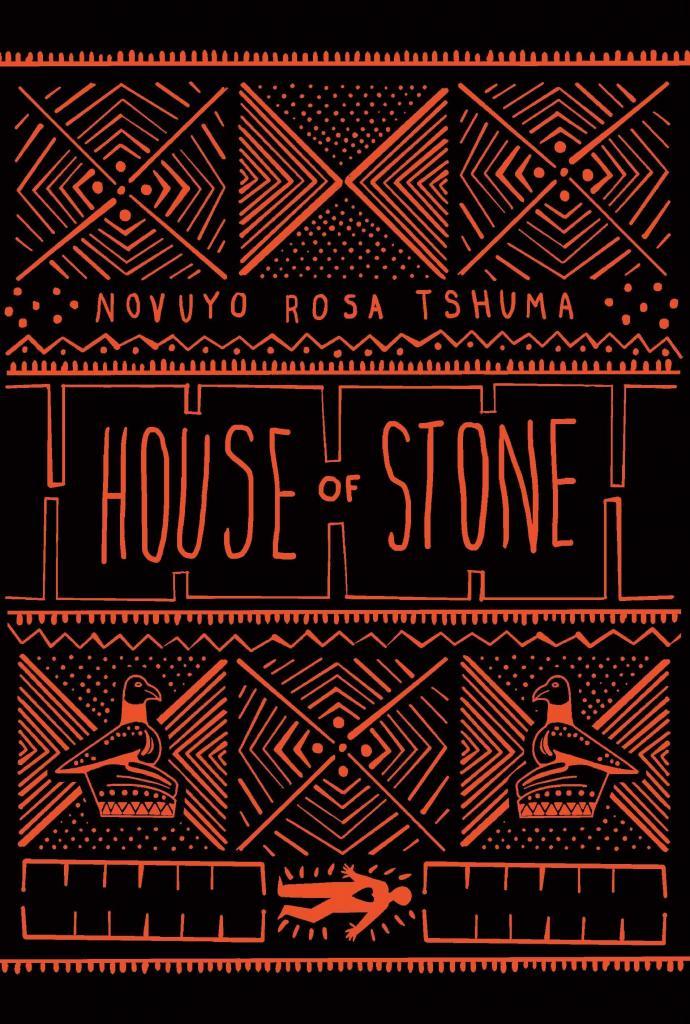

I had an opportunity to interview Zimbabwean writer Novuyo Rosa Tshuma about her new book; House of Stone, which has been shortlisted for the Swansea University International Dylan Thomas Prize.

House of Stone synopsis: In the chronic turmoil of modern Zimbabwe, Abednego and Agnes Mlambo’s teenage son, Bukhosi, has gone missing, and the Mlambos fear the worst. Their enigmatic lodger, Zamani, seems to be their last, best hope for finding him. Since Bukhosi’s disappearance, Zamani has been preternaturally helpful: hanging missing posters in downtown Bulawayo, handing out fliers to passersby, and joining in family prayer vigils with the flamboyant Reverend Pastor from Agnes’s Blessed Anointings church. It’s almost like Zamani is part of the family…

But almost isn’t nearly enough for Zamani. He ingratiates himself with Agnes and feeds alcoholic Abednego’s addiction, desperate to extract their life stories and steep himself in borrowed family history, as keenly aware as any colonialist or power-mad despot that the one who controls the narrative inherits the future. As Abednego wrestles with the ghosts of his past and Agnes seeks solace in a deep-rooted love, their histories converge and each must confront the past to find their place in a new Zimbabwe.

Nkgopoleng Moloi (NM): Can we start with the title of the book; “House of Stone”, what does it allude to?

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (NRT): It’s the translation of the country name “Zimbabwe.” In this way, we can think of it, in the novel, as a sort of allegory of the country, an exploration of Zimbabwe as something dreamed and conjured up and struggling its way into reality.

NM: The book is written from the perspective of ‘Zamani’ – the Mlambo Family lodger; why? What does Zamani’s voice tell us that the other characters cannot?

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (NRT): Zamani is this high-octane consciousness that was both disturbing and delightful to explore. He is on a very specific and existentialist mission that he makes clear to the reader in the opening sentences: “I am a man on a mission. A vocation, call it, to remake the past, and a wish to fashion all that has been into being and becoming.” In this way, he is not just narrating histories, he is reshaping history (or at least attempting to) with the aim of arriving at a different place to his present. The cumulative effect of his mission may well be something beyond him, which builds up and takes a life of its own in the novel.

NM: The battle in Zimbabwe is in large part over its histories. This quote reminds me of what anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot speaks about…that history is the fruit of power, but power itself is never so transparent that its analysis becomes superfluous. How is this work of fiction been able to navigate its way through the different power dynamics in Zimbabwe’s history while also revealing them?

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (NRT): I love Trouillot’s work. I’m actually re-reading his meditations on history in his seminal book —Silencing The Past: Power and the Production of History. There is a multiplicity of voices in House of Stone which is being discovered, directed and channelled by our storyteller, Zamani. He plumbs the lives of the Mlambos —the family he is living with and the lives of everyone close to them; such as the white farmer Thornton, his surrogate father Abednego, Mlambo’s intellectual brother Zacchaeus, and even the dark terror who calls himself Black Jesus. This tension between multiple voices expressing different experiences of the world, which at times overlap, contradict, build upon and complicate one another provides a healthy tension and a chorus of perspectives on history and power.

NM: The synopsis of the novel mentions: He ingratiates himself with Agnes and feeds alcoholic Abednego’s addiction, desperate to extract their life stories and steep himself in borrowed family history…

I’m interested in this idea of borrowed histories, especially because it has so many faces to it. Can you expand on how you think of this notion in the context of this book and in the context of Zimbabwe’s history?

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (NRT): Yes, it’s very interesting how we come into an intimate relationship with our histories, isn’t it? I would go a step further and say Zamani is not just interested in steeping himself in borrowed history, but in doing so until that history becomes his. It is a profound act of faith, the act of speaking oneself into, and believing oneself into existence. Trouillot’s notion about pastness as a position and about us being the contemporaries of history comes to mind—because we access history and memories in our present in ways that go beyond our first-hand experiences of that history and we use that history to shape our (collective) identities. Commemorating historical battles we never experienced and participating in the narratives of those histories, which many times become sacred and very personal, is an example of this. Zimbabwe is deeply embroiled in such projects —as is any space trying to recover from colonialism. Yet, the very act of reclaiming history is political and is very much about wielding power over the present reality and future collective dreams. We see how the past can be edited, manipulated or erased for these purposes in how national history becomes exclusionary and autocratic. In spite of this, the act of revisiting history is an important and indispensable one for any society or people. Zamani is engaged in this very act, of revisiting history, in this way offering and opening alternative ways of entering, engaging with and redirecting this history —ways which trouble Zimbabwe’s mainstream narrative of history.

NM: In terms of process, I’m interested in how you had to think through writing this book; telling the story of a nation’s history through a very personal account.

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (NRT): It was a colossal undertaking, as you can imagine. I worked through seventeen drafts of the novel. The process was informed by my reading and research. It became evident as I read different texts on our history—from history books to novels to oral accounts—how national history is very personal, particularly in places like Zimbabwe that have gone through colonialism. The process of building national identity is also a process of re-inscribing personal identity and there are so many interesting and inevitable tensions in such a process. I discovered varying and at times contradicting versions of the same historical period—such as ex Rhodesians’ memories of the liberation struggle versus Black Africans’ memories of these events. It became important for me that these voices be in conversation, hence the multiplicity of voices in the novel. At the same time, Zamani became an indispensable arranging consciousness; as the novel project took on a life of its own it became evident that it was narrating not only history but also interrogating how that history is made, how it comes to us and how we come to accept it.

NM: Stylistically, I’m interested in how the book is organised; what is the thread that weaves the edges of each of the three books?

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma (NRT): Each book represents a shift in gears for Zamani as he grapples with history and comes up against obstacles in realising his ambitions. In Book One, Zamani concentrates his energies on getting Abednego to give up his reluctant and difficult history. In Book Two, he turns his attention to Mama Agnes, wielding his charm to seduce her into giving up the history he so desperately needs to consume, process and synthesize. However, life happens and he finds himself faced with obstacles. Book Three gives us more insight into Zamani —his history and his motivations. These are the edges of the book and in this structure is an interweaving of stories, ideas, philosophies, ponderings, struggles and dreams.

NM: I’m interested in this idea of silencing the past: at what age did you learn about Gukurahundi?

NRT: Growing up, Gukurahundi was something we knew about but did not know, if that makes sense. It was always in the background—you’d hear whispers here and there about this terrible time during the 80s, right after Zimbabwe’s independence, but talking about that time or even acknowledging it was associated with danger. It was framed as something divisive perpetrated by trouble-makers; those with bad intentions who wanted to divide rather than unite the country. Thus, the act of looking away was compelling. The psychology of it all is very important, I think, because it sheds light on how there has always been great resistance to acknowledging the genocide in Zimbabwe.

NM: In terms of process again; what texts, conversations, pieces of knowledge or other material did you find particularly useful in writing this book?

NRT: I found speaking to my family incredibly useful, not just for what they shared, but also for what they could not share. Those silences, particularly around Gukurahundi, helped me shape the novel and informed my understanding of how history operates and how it is very present in our lives. I eavesdropped on conversations between ex-Rhodesians on their Facebook Pages, and that was useful in helping me think about that period of our country, before independence. The Catholic Church Commission Report on Gukurahundi which was compiled in 1997—about a decade after the genocide—was one of the most harrowing and profound documents. War fiction novels such as The Non-believer’s Journey by Stanley Nyamfukudza were invaluable. Works such as The Tin Drum by Gunter Grass, Carlos Emilio Gadda’s That Awful Mess on the Via Merulana, Dambudzo Marechera’s House of Hunger and Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children were crucial —they helped me think about what I was trying to do with Zimbabwe in House of Stone. And finally, the concept of humor and the range of emotions it can facilitate for us when dealing with colossal histories and events was important for this project. Many readers tell me they opened the novel expecting something very sombre, and were pleasantly surprised by how much they laughed. The surprise and pleasure of laughter and what it can bring forth in the human psyche and in the human spirit, was something I thought about when writing this work.