Africa at the 59th Venice Biennale: An Unequal Vision

While several African countries staged first-ever pavilions, the continent’s presence in Venice was not as strong as one might have expected

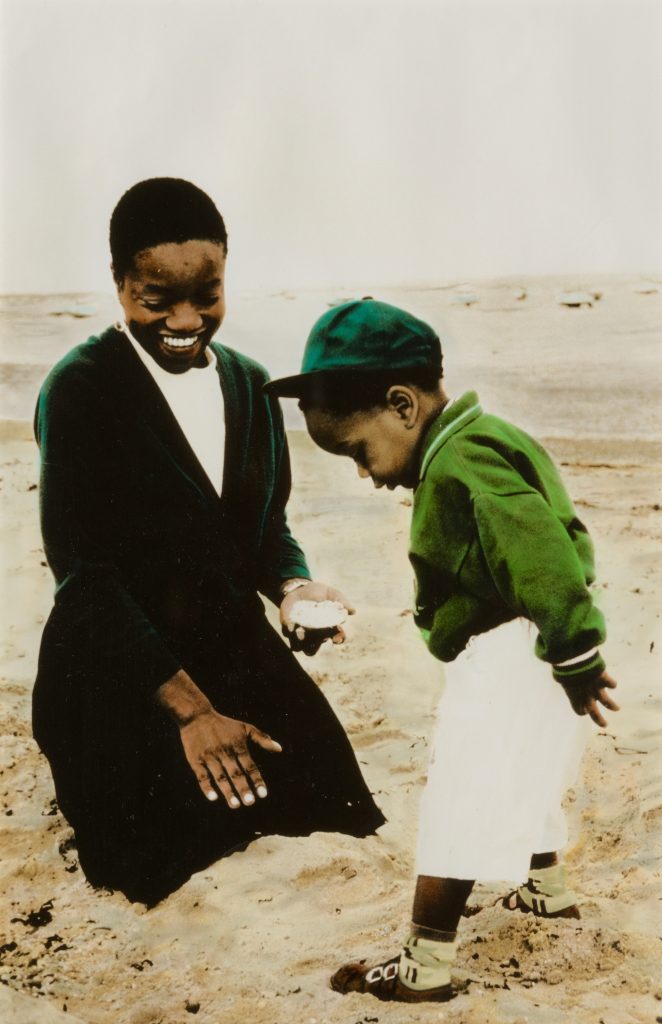

The backs of two painted African figures, an elder man and a younger boy, can be viewed on the large tapestry-like work of Kenyan artist Kaloki Nyamai in the Kenyan Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. The father-and-son-like rendering captures the pair in what seems to be a session of quiet contemplation, almost meditative. In some ways that is the experience desired after arriving by foot to Fabrica 33, the site of an old carpenter’s workshop in Calle Larga dei Boteri in the Cannaregio district of Venice where the Kenyan Pavilion is located. It is situated far away from the Arsenale and Giardini—the main attractions of the 59th Venice Biennale The Milk of Dreams curated by Cecilia Alemani. This year marks the fourth time Kenya is participating at the prestigious art world event, in which Africa, a continent that has garnered great attention from the international art world over the last decade, is still very much underrepresented.

Kenya’s first and second national pavilions at the Venice Biennale pavilion, in 2013 and 2015, caused widespread controversy when they were curated by a team of Italians and showed works by Chinese and Italian artists and only one to two Kenyan artists. The serene feeling one receives while entering into Fabrica 33 is synonymous to the solid representation of the East African nation in Venice after two disastrous showings. When Kenyan Jimmy Ogonga came on board as the curator for the country’s pavilion in 2017 and its showing this year, an exhibition representative of the nation’s art scene was finally had.

This time the East Africa nation is presenting itself in a much sleeker way and with three prominent Kenyan artists—Dickens Otieno, Wanja Kimani and Nyamai—curated by Kenyan Jimmy Ogonga. It is titled Exercises in Conversation and explores the dynamics between participants in a conversation and how such a complex relationship can affect history It was commissioned by Dr. Kiprop Lagat, Kenya’s Minister of Sport, Culture and Heritage. The works, placed around the subtle setting of the Fabrica 33, are hung on the wall like Otieno’s seemingly sparking rendition of the pandemic hazmat suit made from African textile or hung across the room like Kyambi’s textile work that also refers to her Namibian heritage.

Despite the international art world’s fixation on African contemporary art over the past decade, African representation at the Venice Biennale has been greatly lacking, due predominantly to the dearth of funding and resources, and oftentimes also from a lack of interest from respective governments. In 2007 there was only one African pavilion, and now, this year there are nine. Gradually, there has been increased visibility in recent years, particularly in 2015 when the late Nigerian curator, art critic and educator Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019) was curator. Countries that have previously participated, such as Angola, which won the Golden Lion for best national participation in 2013 for its pavilion Luanda, Encyclopedic City, Madagascar, Mozambique and Seychelles, are not present this year.

This year nine nations out of the 55 member States that represent all countries on the African continent showed at the Biennale—out of 80 national participants that are present at the historic Pavilions at the Giardini, in the Arsenale and throughout the city of Venice. The African nations present include Egypt, Namibia, Ghana, Cameroon, Kenya, Uganda, Zimbabwe, South Africa and Ivory Coast. Out of these three participated for the first time: Namibia, Cameroon and Uganda, with the latter being awarded a “Special Mention” by the jury of the Venice Biennale.

“The Biennale Internazionale dell’Arte di Venezia is a stage offering an opportunity for a multiplicity of artistic narratives to be presented and heard,” said Neri Torcello, founder and director of the African Art in Venice Forum (AAVF), which staged its third edition during the opening preview this year. “As the Biennale is perceived by its audience as a global platform, accessibility and representation become even more vital to promote an inclusive creative dialogue in a just society. AAVF, with its discursive, and content partnerships based format is an agile platform to allow this to happen, exactly when the hearts of those sensitive to artistic expression are tuned in to the frequencies of the Venice Biennale.”

This year, in Cecilia Alemani’s The Milk of Dreams, the Biennale’s central exhibition occupying the Arsenale and the Giardini di Castello, 12 artists were chosen from the African continent out of the 213 artists from 58 countries that Alemani selected. These included South African Igshaan Adams, Sudanese-Danish Monira Al Qadiri, Ibrahim El-Salahi from Sudan, Kudzanai-Violet Hwami from Zimbabwe, South African Bronwyn Katz, Antoinette Lubaki from the Democratic Republic Congo, French-Egyptian Amy Nimr, Kenyan Magdalene Odundo, Ethiopian Elias Sime and Portia Zvavahera from Zimbabwe.

Standout pavilions this year included Ivory Coast, participating for the second time since its debut in 2013. It showed Dreams of a Story, a presentation of ethereal works oscillating between a surrealistic dream world and everyday life in the West African nation, with the participation of artists such as Aboudia, Armand Boua, Frédéric Bruly Bouabré, Aron Demetz, Laetitia Ky and Yeanzi. Curated by Italians Massimo Scaringella and Alessandro Romanini with support from the Ministry of Culture and Arts and Entertainment Industry of Ivory Coast and the Italian Embassy of Ivory Coast, the heightened abstract mixed media canvases of Boua, with their inclusion of newspaper clippings, hang next to the abstract lightboxes of Yeanzi replete with depictions of various local icons and symbols as well as captivating profiles of unknown figures. Pulsating with movement, color, brushstrokes and lines are the abstract expressionist canvases of Aboudia , one of the nation’s most recognizable stars. His canvases document the street scenes of his hometown of Abidjan with graffiti-like renderings of daily life, people and children, and include his recurring skull, bullet and soldier motifs that point to violence and trauma—a nod to post-election conflict that took place in the capital in 2011. The works are assertive, strong and vulnerable in ways that speak to an Africa in crisis and to the fraying of the continent’s social fabric in its post-colonial years.

Zimbabwe, by contrast, is participating for the sixth time at the Biennale. Yet its pavilion, titled i did not leave a sign?, and featuring four artists— Kresiah Mukwazhi, Wallen Mapondera, Terrence Musekiwa and Ronald Muchatuta—features a loosely held together show that is disappointing in formal content and themes. Curated by Fadzai Veronica Muchemwa and commissioned by Raphael Chikukwa, Mukwazhi’s expansive abstract expressionist work with its vibrant hues and animated series of figures prompts the spectator to stay for a while and ponder the rhythmic movement and figures depicted. It is the star of the show. In other rooms, mixed media installation works, some including figurines made of pink, cream and white bras holding Kalashnikovs or large phantom like figures in another room made of dozens of old black wires, give off an unsettling and incomplete feel. The goal of Muchemwa is to explore tales of dispersion and migration, knowledge, science and technology, as ways to rebel against the uncertainties of organized religion.

A gem at the biennale this year was Uganda’s pavilion, making its debut in Venice, and for which it received a “Special Mention” for national participation from the Biennale’s jury. Titled Radiance – They Dream in Time, the exhibition was curated by The Ministry of Gender, Labor and Social Development, which officially supported the pavilion. Juliana Naumo Kuruhiira served as the pavilion’s commissioner, with Tanzanian-born British taking up the role curator, Shaheen Merali, and features works by Kampala-based artists Acaye Kerunen and Collin Sekajugo. Tradition and contemporary culture are elegantly paired in dialogue through the two artists’ work. Sekajugo’s paintings portray poignant subjects in rich hues in everyday and public settings, whereas Kerunen’s work resurrects local Ugandan craftsmanship and heritage in her contemporary installations made of natural and reusable materials such as swamp grown fibers and polyethene bags. Their work, when paired side by side, introduces the diversity in heritage and contemporary culture in present-day Uganda.

“Uganda has barely been represented on the international art stage,” said Sekajugo. “A country whose people I personally consider resilient and persevering, has seen so many ups and downs during its artistic revolution. From the country’s turbulent past to present day sociopolitical struggles, creative production has taken different shapes where platforms for self-expression have often been limited to a few brave practitioners. I strongly believe that this showcase will only open more doors for our creativities.”

While Namibia’s first-ever pavilion was embroiled in scandal a week before the Biennale opened, with its main sponsor, luxury travel operator Abercrombie and Kent, and its patron Monica Cembrola pulling out because of what they viewed as a misrepresentation of the Namibian art scene (the pavilion features the work of one artist who is making his debut in Venice and goes by the pseudonym RENN), the Egyptian pavilion, which focuses on digital art and features work by Mohamed Shoukry, Weaam El Masry, and Ahmed El Shaer, curiously remained closed during the first few days of public viewing due to technical difficulties.

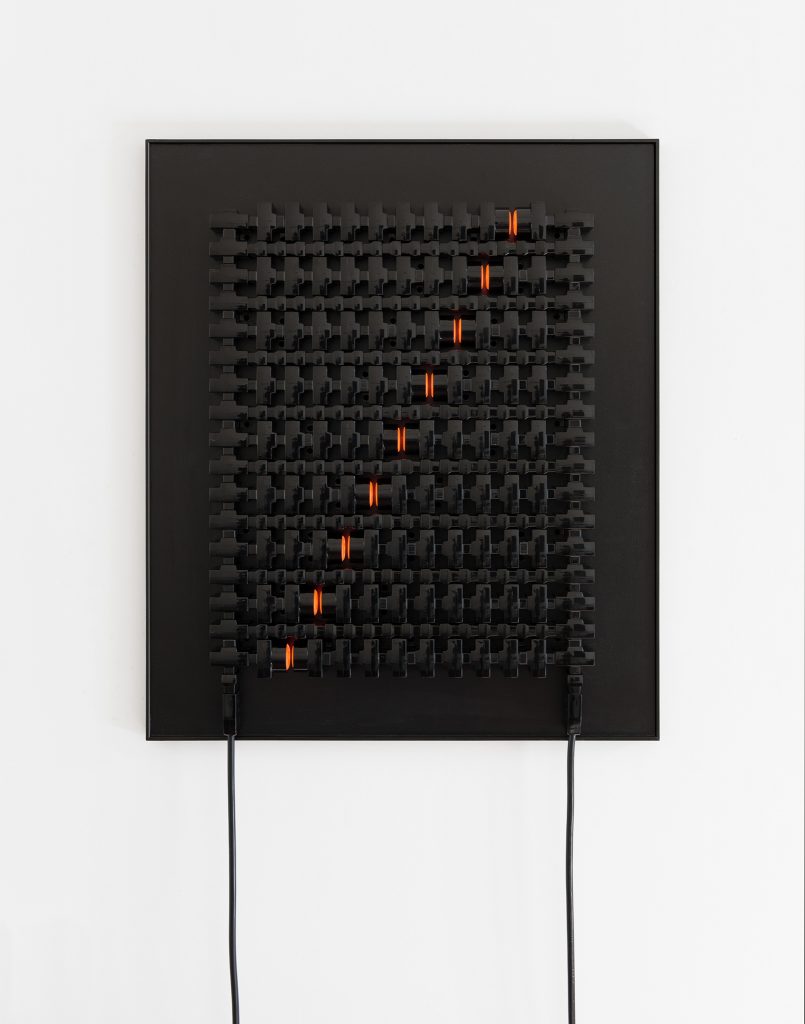

For Cameroon’s first-ever pavilion, which took place in two locations, within the loggia of the Liceo Artistico Statale Michelangelo in the Guggenheim Museum in the Dorsoduro district of Venice and at the Palazzo Ca’ Bernardo. The former presents IRL (“in real life”) art by four Cameroonian (Francis Nathan Abiamba, Angéle Etoundi Essamba, Justine Gaga, and Salifou Lindou) paired with four international artists (Shay Frisch, Umberto Mariani, Matteo Mezzadri, Jorge R. Pombo). The works, done in a variety of media, including photography, installation, painting and sound, offer an eerie portrayal of the west-central African nation. While the works of Douala-based Salifou Lindou standout for their technical precision, color and movement, in the center of the loggia is Transfiguration (2022) by Justine Gaga, a Cameroonian sculptor and video artist. Her haunting installation consists of a group of metal rods akin to totem poles with circular metal objects as heads and long patterned scarves hanging from the top. On the metal rods are written words in French such as liberalism, violence, capitalism and fiction.

It is the pavilion’s second location at the Palazzo Ca’ Bernardo that is perplexing. It presents an NFT show, arguably the first at the Venice Biennale, organized by Global Crypto Art DAO, a new collective that raises money to support artists making the transition into the world of crypto. Featured are works by artists from over 20 countries, notably Germany, China, and the US, but not Cameroon.

Stationed prominently within the Arsenale, one of the biennale’s most coveted venues, is the Ghana Pavilion. Its exhibition Black Star – The Museum as Freedom follows the West African nation’s acclaimed debut in 2019 and features the work of Ghanaian artists Na Chainkua Reindorf and Afroscope and Brazilian Diego Araúja who is interested in the connections between Ghana and his homeland. It has the same curator as the 2019 pavilion, Nana Oforiatta Ayim, who is also the director of ANO Institute of Arts and Knowledge in Accra and director-at-large of Ghana’s Museums and Cultural Heritage.

While underwhelming compared to the size, vision and quality of works shown at Ghana’s first presentation in Venice, what is notable is the theme and the diversity of mediums used—from works on canvas to technology and installation. The works on display support the idea of the Black Star that symbolizes Ghana through its flag and most important monument, the Black Star Gate, part of Accra’s Independence Square now known as the Black Star Square, which is topped with the Black Star of Africa—a five-pointed star that represents the continent with a particular nod to Ghana, which in 1957 was the first Sub-Saharan country to break free from colonial year when it declared independence from Great Britain. The Black Star, as the exhibition further emphasizes, also connects Africa with its diasporas through Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey’s Black Star Line and his resulting Back-to-Africa movement. The Black Star now goes beyond Ghana: it is symbolic of all people of African descent wishing to make their way home to the continent.

“Last year we showed the superstars of the Ghanaian art scene and this time I really wanted to look at the future-builders,” said Oforiatta Ayim. “These artists for me are ones that are creating new models through language, narratives and technology. Last time we looked at the legacies of the past on the present and this one is much more looking at how we create new futures.”

While Africa might not yet have an adequate representation of the richness of its evolving art scenes through a more prominent showing of national pavilions at the Venice Biennale, an increase in the showing of artists from the continent and its diasporas at the world’s most prominent art event tell of a new chapter on the horizon for art from the continent on the international stage. Still, much work needs to done.