Africa’s Biggest Art Fair Tests The Online Environment

The Investec Cape Town Art Fair’s first online event, might not have attracted the numbers or sales, but offered an exciting spread of art from the continent’s newcomers.

It’s hard to gauge the temperature of an online art fair. You don’t get to chat to gallerists or their staff on the floor, experience the throng on opening night or spy which gallery sold out before the fair ended. Online art fairs are different animals in every sense. Over a year into the online art fairs game, we also know now that they are not that effective at attracting sales. As the UBS Global Art Report 2021 indicated in 2020 art dealers only derived 13% of their income from fairs whereas a year previously they generated 43% of all sales from them.

Given a degree of online fatigue is likely to have set in, and the glut of online art content that is out there and art buyers attention turning to real live art fairs – the recent Armory and upcoming Art Basel, Frieze London and 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair – interest in online art fairs might be waning.

This is the context in which Investec Cape Town Art Fair (ICTAF) launched its first digital platform last week and by all accounts, from gallerists and the organisers themselves, there wasn’t as much engagement and sales as had been expected.

Owned by the Italian events company Fiera Milano, this fair is the largest and certainly the most ‘international’ one on the African continent. Not only does this fair attract a large contingent of collectors from Europe, but almost 40% of the commercial galleries that participated last year were European-based.

Their last live fair – which took place at the Cape Town International Convention Centre in February 2020 – boasted over 100 exhibition stands and the participation of 72 commercial galleries – the rest were non-profits, media publications or printing studios. With all the ancillary events that have blossomed up around this art fair – with the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art, the Norval Foundation, the A4, Iziko South African National Art Gallery all putting on a strong programme to entertain all the art visitors to the city, this annual event has fast become a must-do one on the African continent.

How is it possible to translate this buzz, activity and all the sales it generates for the dealers on an online portal? It’s an impossible task and this may be why Fiera Milano were hesitant to launch an online version in February this year.

“People are finding their way around the digital world and now that is part of the art world but we really wanted to host a physical fair,” commented Sophie Lalonde, head of VIPs and partnerships at ICTAF.

Visitors and number of sales

This online edition with technology facilitated by Art Shell was paired with the Milan-based Miart, another art event staged by the Italian Fiera Milano. “We wanted to leverage Fiero Milano-owned fairs and the database of VIPS… we can give more access to other galleries (from outside SA) and allow our galleries access to their VIPs,” says Lelonde.

Exactly how much ‘eye’ traffic flowed from Miart to ICTAF is not certain. Some of the South African galleries – Worldart, Ebony/Curated and Southern Guild – all reported that they did virtually meet some new collectors. However, based on the figures, the majority of visitors to the website – 69% – were South African-based, while the rest – 31% – hailed from other parts of the world, according to Fiera Milano.

All in all, visitor numbers to the online fair were substantially lower than the foot-traffic at their 2020 live fair last year. While last year brought 22 000 visitors to the art fair, they only attracted 3415 unique users. This is unusual, given the Joburg-based Turbine Art Fair attracted double the number of visitors to their online version last year.

These low visitor numbers reflected in a reportedly poor enquiry rate.

“Most of us have only had a handful of enquiries unfortunately,” observed Julie Taylor of the Joburg-based Guns & Rain. Danda Jaroljmek of the Nairobi-based Circle Art Gallery was very disappointed.“We had no interest, no contacts and no sales,” she reported.

This may have been due to the live ‘chat’ device, which one gallerist, who wished to remain anonymous, observed had “confused a few visitors. Only experienced collectors knew to provide emails for follow up, and while we of course requested emails for everyone making requests, we lost some because those people where possibly not online at the time. I think an easier interface was required.’

Afronova, Ecletica, Suburbia, Smac, Ebony/Curated, Worldart galleries and the Arthrob non-profit platform, all reported sales, according to Fiera Milano.

As of Monday, some galleries, Southern Guild, Melrose Gallery, MmArt House – reported that they had yet to secure a sale.

“It’s a bit soon to say anything or nothing sold but there was quite a lot of engagement and interest to get a preview VIP ticket,” said Trevyn McGowan of Cape Town-based Southern Guild.

Yet, some gallerists, such as Busi Tsiki, from MmArthouse, who have yet to participate in a live ICTAF event, found their participation as a useful means of testing out which artists they should bring to the fair when it takes place in real life in February 2022.

“It helped solidify our direction and strategy for the physical fairs and for the artists we work with,” said Tsiki. “There is a benefit in visibility to a client that you would not have otherwise reached. As a small gallery, participation also keeps us relevant in the art community,” she added.

Other gallerists seemed to concur with this view – that online fairs were less about sales and more about maintaining visibility.

“Events like this present an opportunity to promote and actual sales realise over a longer period than just the actual fair days, so it is too early to tell how successful it was. I am happy with the result and it definitely was worth the effort,” said Charl Bezuidenhout, director of Cape Town-based Worldart.

The content of the art on the online platform seemed to align with this perspective with many of the galleries, not bringing new works to the fair but rather using the platform to market existing shows being staged in their galleries. This was the case with Stevenson and Blank Projects among others from South Africa and Osart, the Milan based gallery, which all presented solo exhibitions that are currently or have been staged in their galleries.

This to some degree has been a characteristic of online fairs – the works on offer are not new – having been shown on other online portals or exhibitions. This has perhaps contributed to less engagement and sales on these platforms as the drive to see and acquire new works under pressure is what has made live art fairs so successful. In the past, aside from solo booths, most galleries tend to offer works from all their ‘star’ artists at art fairs.

The content of the fair

© rhizome gallery.

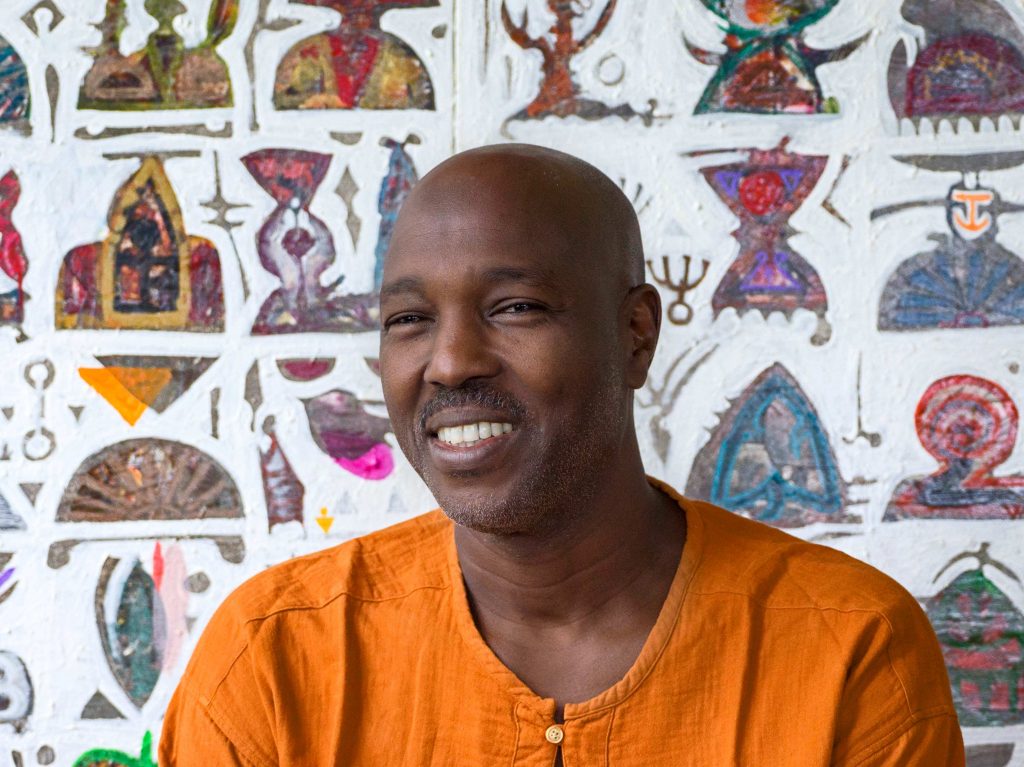

There was a lot of art and other content – videos and interviews – to view. This online fair accommodated 54 exhibitors of which 49 are bona-fide commercial galleries. In this way the online fair was almost half the size as the live one. There was a smaller contingent of European-based galleries. Artistic expression from Northern Africa was channelled through some new participants, African Arty (Casablanca/France), Mashrabia (Cairo) and Rhizome (Algiers).

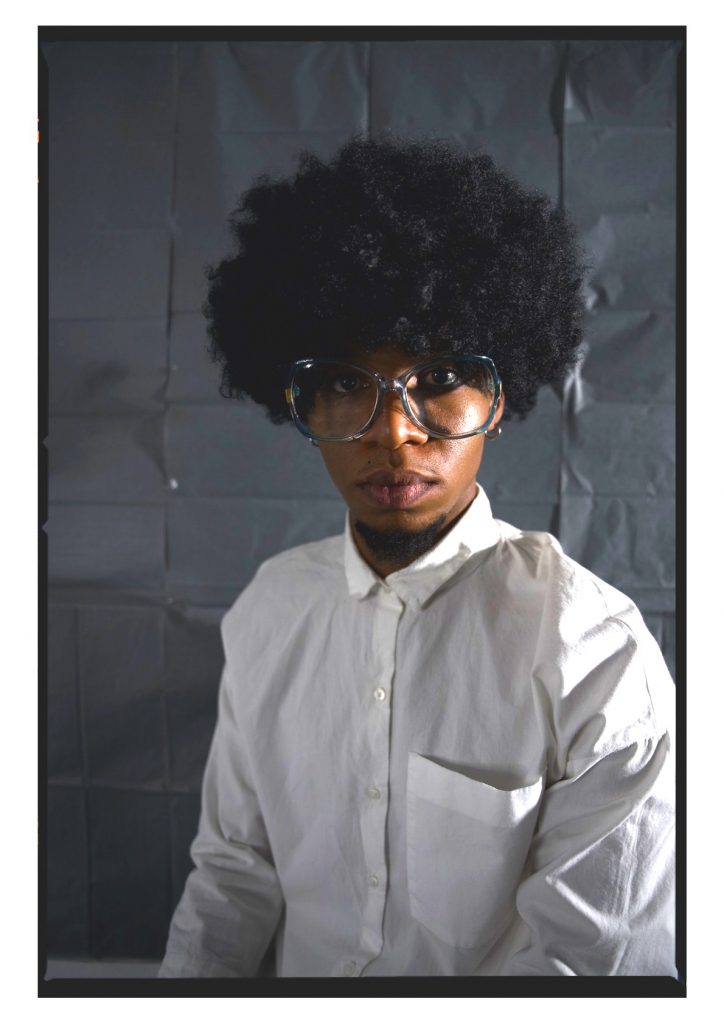

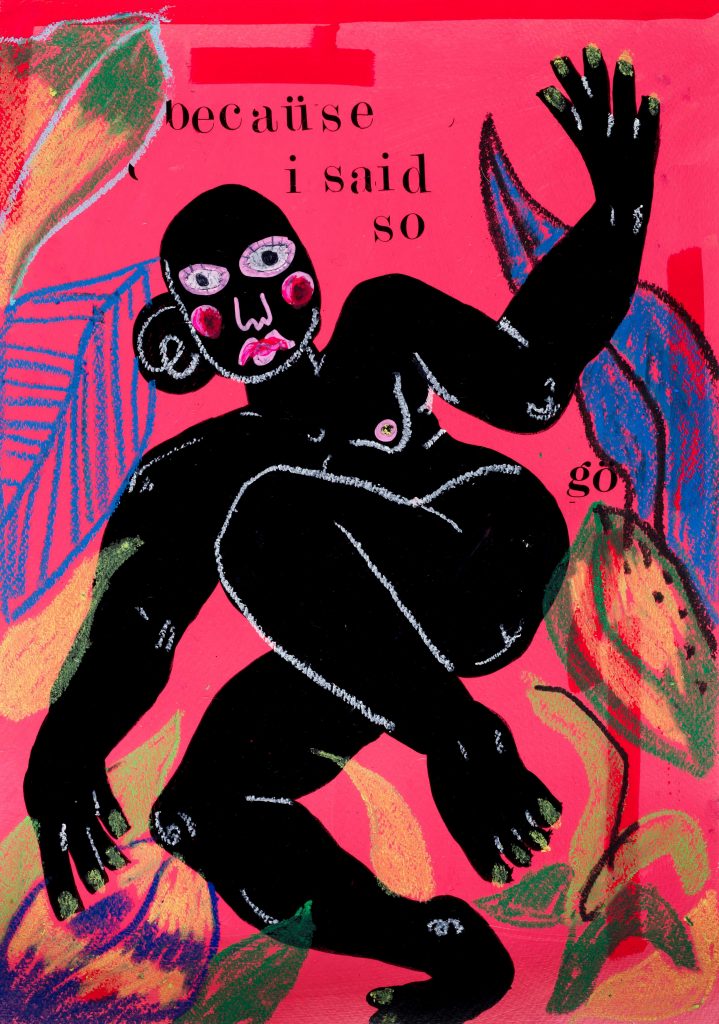

An abundance of black portraiture was to be found, given the heightened interest in this genre on the auction circuit and in the US. There was interest in some newcomers working in this vein such as by the young Zimbabwean artist Tafadzwa Tega whose use of flat pattern and colour generated sales for Ebony/Curated.

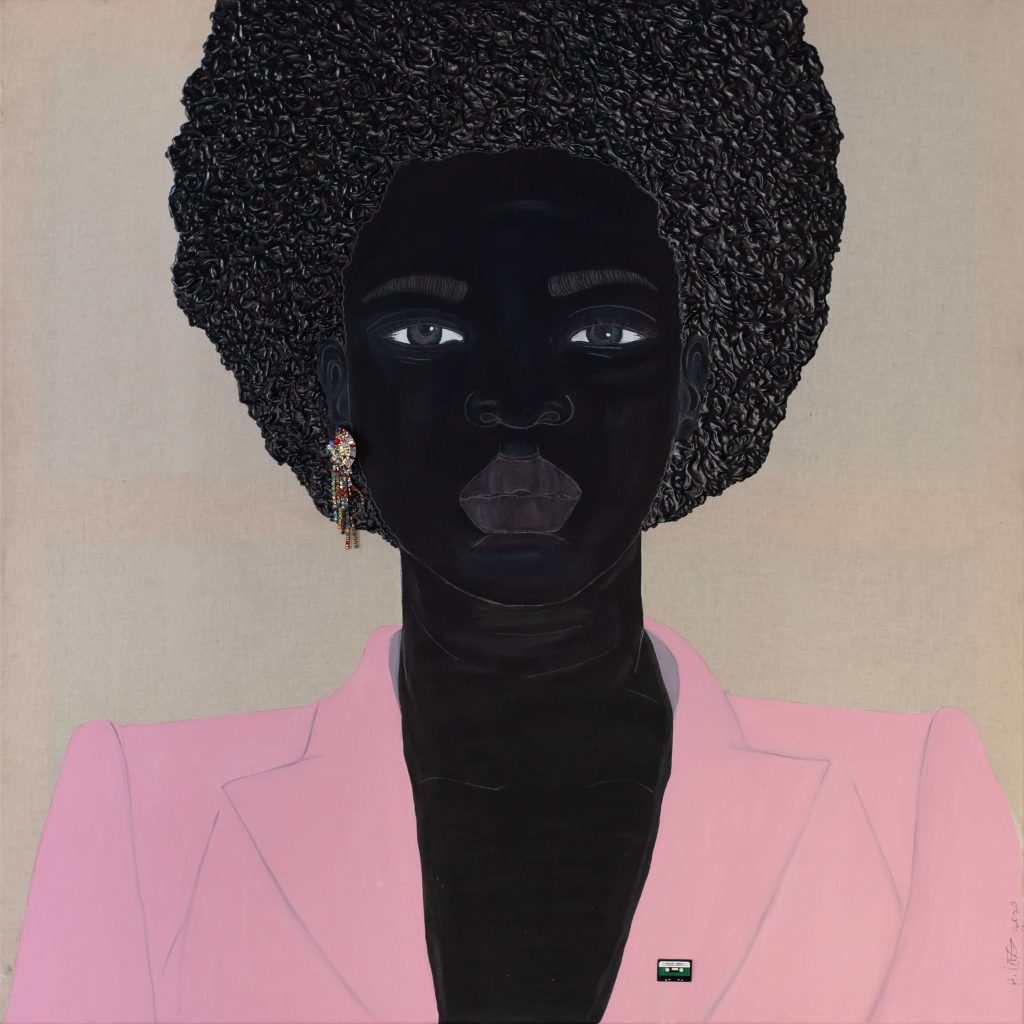

African patterns and prints infused the portraiture of Angolan artist’s Osvaldo Ferreira’s paintings offered by This is not a White Cube. Cape Town-based Christopher Moller focussed on portraits of black subjects by a range of artists from different countries, such as Idris Habib and Daniel Tetteh Nartey both from Ghana, Tjaša Rener from Slovenia and Barry Usufu from Nigeria. The pop aesthetic – flat, bold colours and stylisation dominated these artists approaches.

Artists whose works do well on or are features of dedicated African auctions such as William Kentridge, Franck Kemkeng Noah, and Zemba Luzamba, Goncaldo Mabunda and Esther Mahlangu, were naturally offered by galleries. It was works and presentations by some newcomers to the art scene that were more interesting to discover such as Patrick Akpojotor’s (Nigeria) Escheresque charcoal drawings, or Marwan El Gamal’s (Egypt) dense utopian landscapes, or Bahati Simoens’s (Burundi) headless subjects presenting a wry twist on the portraiture theme. Daniel Malan was perhaps the only artist presenting an NFT (non-fungible token) work for sale on OpenSea via the fair. The animated underwater scene depicted in his NFT work related to his paintings offered by Plot Gallery, resulting in a viable integration between object and digital based art.

This draws attention to perhaps one of the benefits of online art fairs in the African art market – due to the fact that there is less risk and costs involved in presenting new emerging artists work and there are less barriers for small upcoming galleries and spaces to participate in an established art fair such as this, they present the opportunity to really make some new discoveries. This is something that had become increasingly harder in the live events.

Images in the slideshow: Stella by Idris Habib featured on Christopher Moller’s virtual stand; ZiziphoPoswa’s Magodi Nokwanda offered by Souther Guild. Picture by Christof van der Walt.