Ernest Mancoba between racial marginality and african modernity at the Pompidou Centre

26/06/2019 - 23/09/2019The Centre Pompidou continues its work to shed light on non-Western artists often little known to the general public. After the Russian avant-gardes, Polish artists Katarzyna Kobro and Wladyslaw Strzeminski and Cuban artist Wifredo Lam, it will be the turn of South-African artist Ernest Mancoba and Danish artist Sonja Ferlov Mancoba, exiled in Paris for almost the entire length of their respective careers, to be exhibited in Galerie 0 and the Galerie d’art graphique from June 26th to September 23rd 2019. Married in Paris and sharing the same Parisian studio, Ernest Mancoba and Sonja Ferlov Mancoba will be given top billing by the Centre Pompidou in two distinct spaces, in order to pay tribute to the breadth of their practices, inseparable and yet singular.

The exhibition dedicated to Ernest Mancoba is unprecedented, opening up considerable thought on a figure at the heart of debates on racial marginality and erasure, in a reciprocal redefinition of modernities (establishing an African modernity, integrating Africa into European modernities, etc.) It is a way for the Centre Pompidou to present a major career that has remained absent from previous accounts on these issues in France (“Magiciens de la terre,” “Africa Remix”), as well as to boldly affirm its desire to organise non-western artistic retrospectives and retrace the historical depth of certain geographic areas.

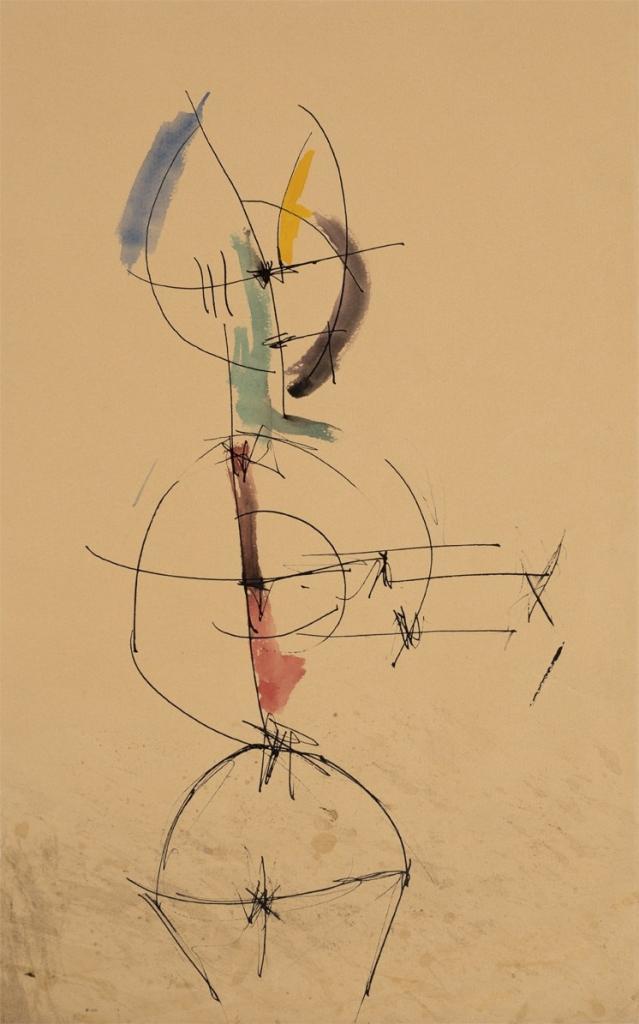

Collection Mikael Andersen. © Courtesy of the Estate of Ferlov Mancoba

Ernest Mancoba (1904 – 2002) was a French-South-African artist, writer and thinker whose life spanned the whole of the 20th century. A painter, sculptor and draftsman, he was a fascinating figure in a class of his own. This is shown in the scope of his historic, transnational career in societies that were repressive or still averse to the idea of a black man with an independent career. His visual language, associated with the CoBrA movement but ever suspended in unresolved tension between figuration and abstraction, is also a specificity of his work. The exhibition proposes, for the first time in France, to retrace this career that has been erased by both racism and a life spent in isolation, as well as the complexity of his artistic work that strove to reconcile political and formal worlds, dissolved in a universal hope at the crossroads of Christianity, Marxism and Ubuntu philosophy (a theory of reconciliation championed by Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu, in particular).

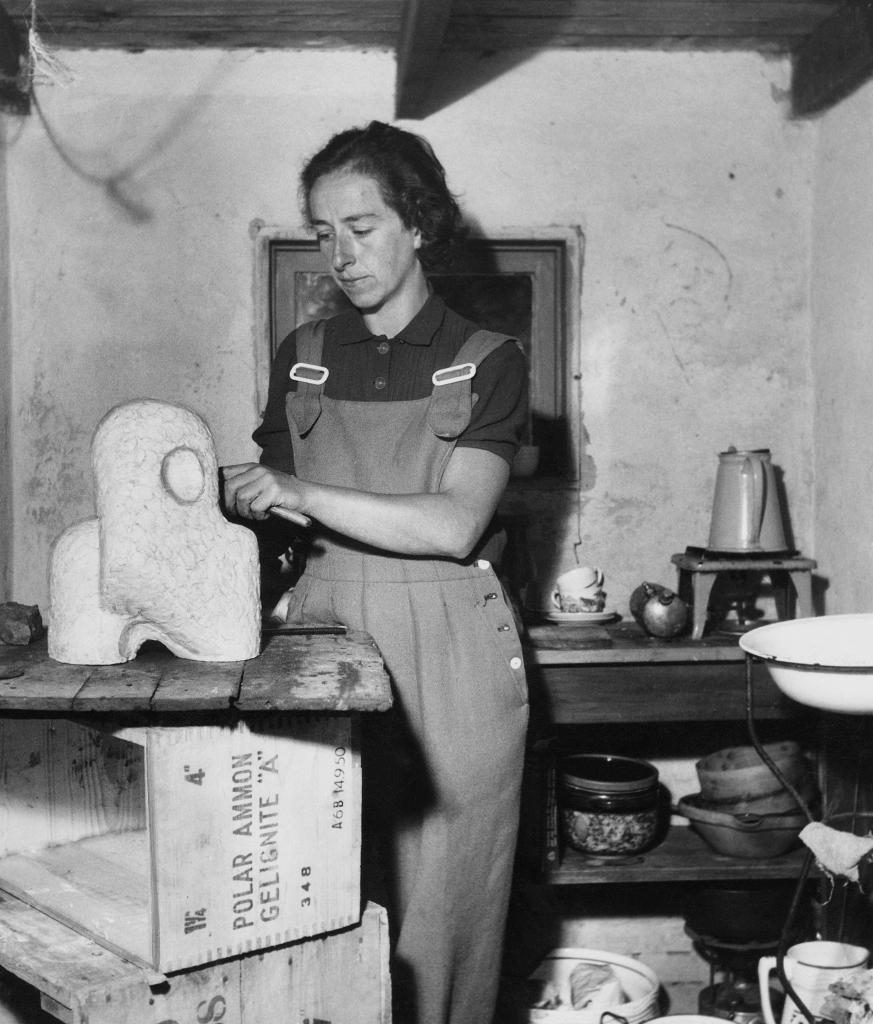

After fleeing the apartheid in South Africa, which prohibited him from pursuing a career as an artist, Ernest Mancoba arrived in France in 1938 where he was soon sent to a German labour camp due to his British citizenship. During World War II he married Sonja Ferlov, a Danish colleague whom he met in one of his decorative art classes. After the war, they went to Denmark together for five years where they joined the early CoBrA movement through their friend Asger Jorn. CoBrA combined all of Mancoba’s deepest interests present in his work since his time in South Africa : the importance of soliciting the subconscious, the necessity of returning to society’s spiritual roots through folklore, faith in society’s materialistic transformation and the goal of making art universal and not just Pan-Nordic. Mancoba did not remained long with the group, however ; his carefully constructed and semantic abstraction was disputed, and underlying racism relegated him to the status of an invisible man or “black dot” of the movement.

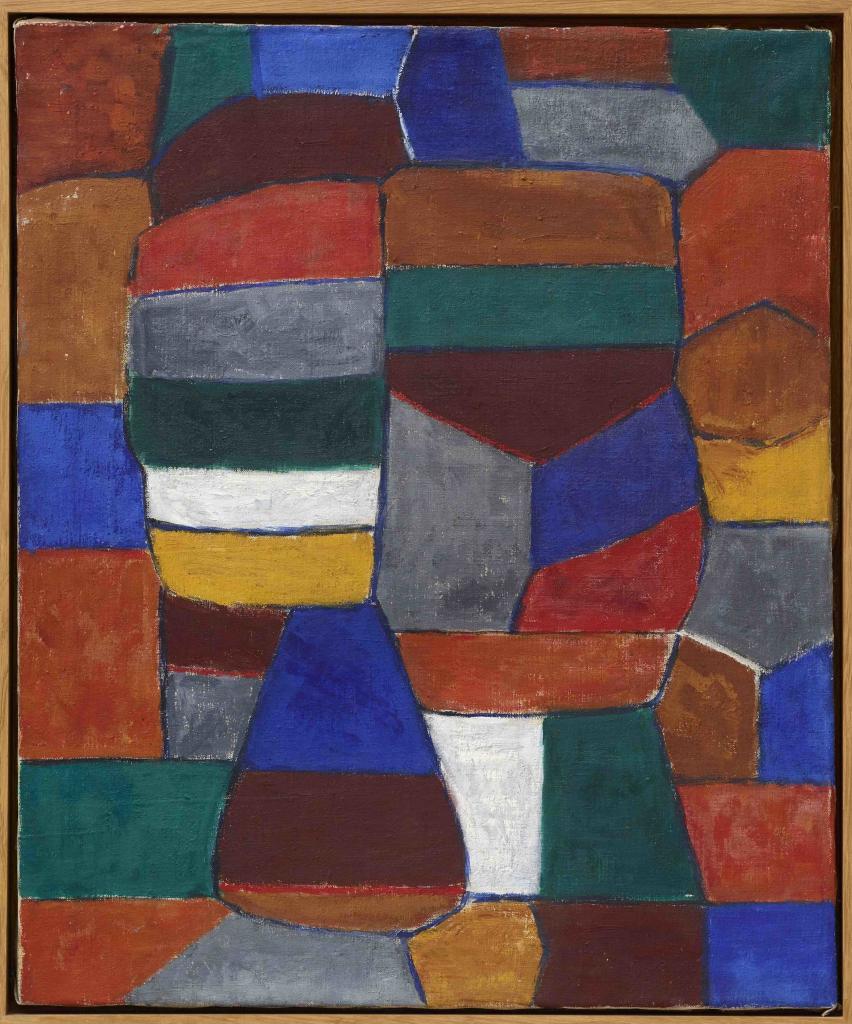

© Courtesy of the Estate of Ferlov Mancoba

Returning to France, Mancoba and Ferlov opted for a life of solitude, a choice which proved definitive, and moved to Oigny-en-Valois. They accompanied their artistic practice with political and ethical activism which they hoped to share with their artistic entourage, without ever succeeding. In the early the 1960s the couple found a home near Montparnasse where they spent the rest of their lives. A store on the street served as their studio, which was divided in two using a sheet and where their artistic practices complemented one another and developed mutually.

The 1970s saw the only exhibitions dedicated to Mancoba during his lifetime in the West : in Denmark in 1969, at the Aarhus Kunstmuseum and the Holstebro Kunstmuseum and, in 1977, at the Københavns Kunstforening in Copenhagen, the Fyns Stifts Kunstmuseum in Odense and the Silkeborg Kunstmuseum. After the death of Ferlov (December 17, 1984), the 1980s represented a period of mourning and the gradual emergence of a universal language that attempted to translate what the artist called “the unspeakable” : Mancoba’s last formal artistic burst, or more likely, his greatest achievement.

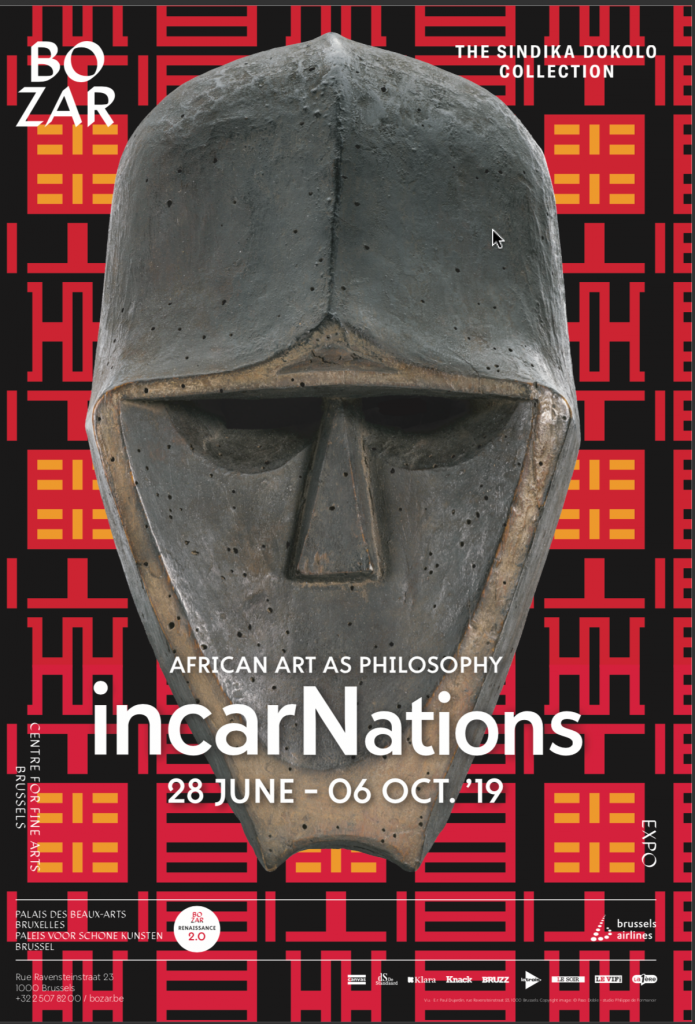

In 1983 Elza Miles, a South-African academic, discovered her compatriot’s work in the “CoBrA” exhibition held that year at the City of Paris Musée National d’Art Moderne and attempted to meet him. In 1994, she published the only monograph written about the artist in his lifetime, Lifeline Out of Africa, the Art of Ernest Mancoba, and organized an exhibition in parallel in Johannesburg just after the end of apartheid. In 1999, Okwui Enwezor included Mancoba in the visionary exhibition The Short Century, Independence and Liberation Movements in Africa 1945-1994. Hans-Ulrich Obrist tracked him down in Paris to conduct an interview that was first published in 2003 in the journal Nka, journal of contemporary African art, and which has since become famous. It was republished many times over, inaugurating a series of major articles on the role of the artist in the accounts of modernity in general.

© Courtesy of the Estate of Ferlov Mancoba

The exhibition evokes the tension between the intellectual contribution of an artist and writer trained in journalism, and the implementation of a secret and poetic mode of expression in his work based on the synesthesic notion of “connections.” Designed as an initiatory experience, the exhibition begins with a sound threshold from which Mancoba’s voice resonates, leading into an immersive, intimate room dedicated to his successive battles with material and spatial limitations throughout his life in exile.

Norval Foundation, Cape Town

© Courtesy of the Estate of Ferlov Mancoba

A system of echoes spreads throughout the exhibition through the work of the artist Kemange Wa Lehulere (born in 1984 in Cape Town), whose work is simultaneously poetic and political and is imbued with his shared quest with Mancoba for a language above language, giving prominence to that which cannot be expressed, such as collective repression.

From an initial matrix dominated by Mancoba’s tireless search for the “central figure”, different thematic- chronological chapters spread out throughout the exhibition, designed as motifs in a unified dance where only one image seems to move. In 1938, when Mancoba arrived in Paris from Cape Town via London, he decided to learn how to dance and bought a manual to practise in his room near Montparnasse.

One evening, a friend took him to the Bal Nègre, where his was clearly ill at ease. To the repeated entreaties of his friend to come and dance, he retorted firmly: “I shall dance in another society”. However, in the book dedicated to the artist by the academic Elza Miles, Mancoba evokes dance as the ultimate level of communication. This rhythmic dance is without a doubt at work in the artist’s practice, where the figure is constantly turning round and round. It is precisely this unresolved tension between historic oppression and humanistic and poetic resistance, between an impossible life and the liberated work of Ernest Mancoba, that will be addressed in this exhibition.

A parallel program of contemporary activities and meetings will be held during the exhibition to further explore an unprecedented collection of archive material and question the complexities of a career at the crossroads of multiple cultures and a variety of formal worlds.

« I want to sum up and put in a nutshell the program of our spiritual responsibility as artists. As artists we have followed the national academies, and each is national, and the point of this is political. Each country follows the method by which each country will survive and these countries have never been united.England, Denmark, France. Each country has its different ways of looking. They agreed that in the Occident they constitute the whole of humanity, each other country, the rest of the world are trying in vain to become like Europe. In my memoirs I am trying to show my struggle to get the rest of the third world included in part of all humanity. The third world has to be taken into consideration as it exists. I want that this separation this apartheid has to be pushed aside and that all human species have to hang together hand in hand that’s all »

Ernest Mancoba

The research carried out for this exhibition led to revelation of substantial archive material to be categorised and indexed in view of a monographic publication for the fall of 2019.