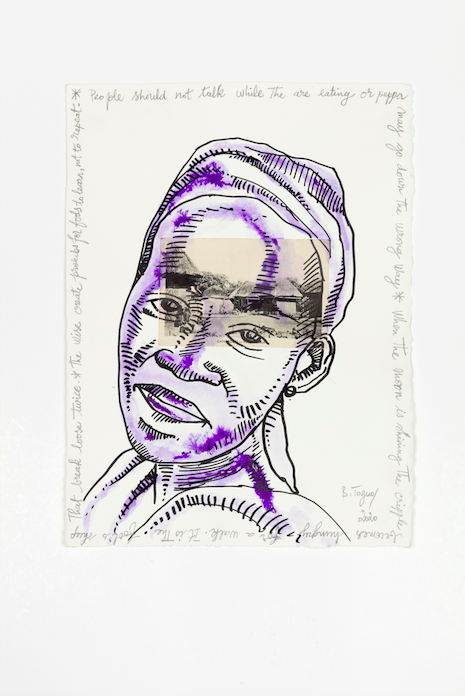

Face to face with something commensurate to our capacity to feel

Mixed media on paper

38 x 29cm

“For a transitory enchanted moment, man must have held his breath in the presence of this continent, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation he neither understood nor desired, face to face for the last time in history with something commensurate to his capacity for wonder.”

Through this quote, author John Green noted how the narrator in the famous American novel; The Great Gatsby points us towards the idea of wonder —more appropriately humanity’s capacity for wonder. It’s safe to say that in this age very few things are proportionate with humanity’s capacity for wonder but even more so, very few things are proportionate with our capacity to feel.

I am not suggesting that our capacity to feel has diminished or shrunk, what I am suggesting is that fewer and fewer things have the ability to move us emotionally. As the rate at which we are being stimulated, entertained, challenged, provoked etc. continues to increase so the rate of affect or affectivity declines. Here we are building on the idea of affect as understood by French philosophers of the last century —affect as the sense of what is felt or as the mental activity required to make sense of the world.

Mixed media on paper

38 x 29cm

I’m interested in these moments of affectivity that are experienced through a glimpse into someone else’s world; moments that occur through literature, music or art, where one finds oneself understanding or at least wanting to understand the experiences of someone else. Bilongue (an exhibition staged at Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town) is Barthélémy Toguo’s attempt at understanding the experiences of others, where the artist is allowing himself to struggle with these experiences that are too complex to synthesise. The poverty of language would have us identify this as empathy however I think we should perhaps not be so quick to settle for this type of language.

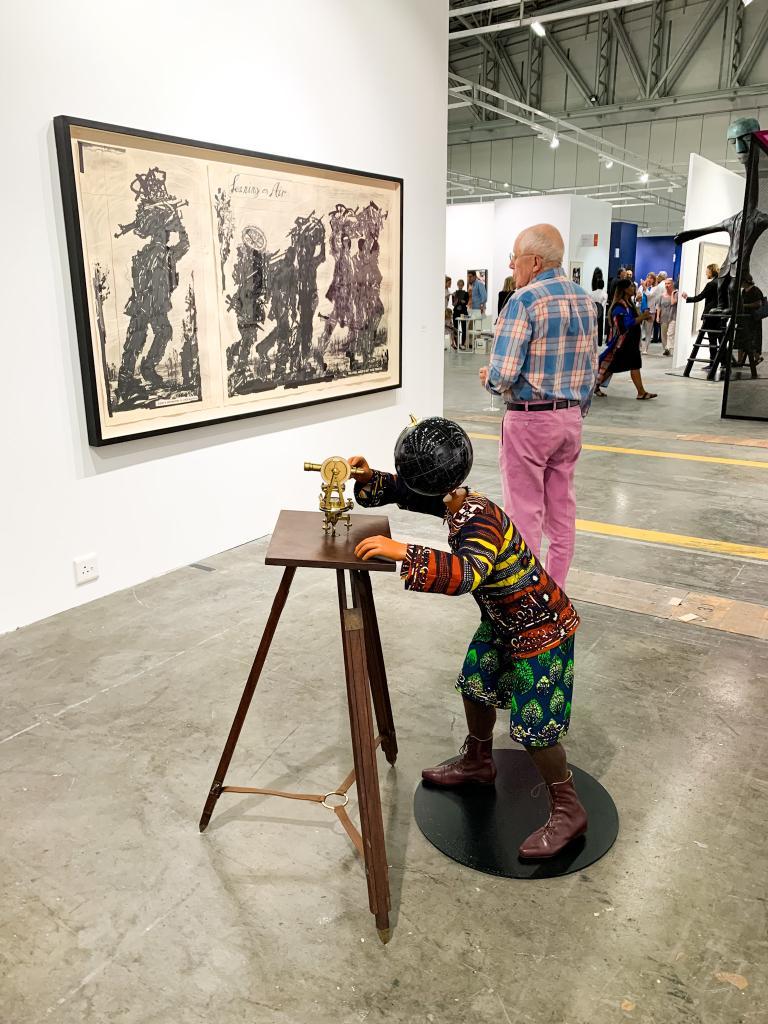

Toguo’s exhibition is created to pay homage to the experiences of the residents of a settlement in Douala, Cameroon; Bilongue. These are people who are largely facing difficult living conditions. The exhibition brings us face to face with portraits of residents of Bilongue and we are confronted with thoughts, feelings, pleasures and displeasures. Drawings on paper are presented together with wood carvings, where lines are chiselled onto the Zingana wood from the Zingana tree of West Africa ( also known as Microberlinia Brazzavillensis). The lines form contours of the distinct features of each of Toguo’s subjects. We see the artist’s hand through his carved marks on the wood but we also see nature’s marks through the phloem of the tree. The illusion of verticality and deep contouring are heightened by this intersection of natural imprint on the inner bark together with Toguo’s own marks.

Zingana Wood

70 x 51.5 x 3.5cm

Walking through Togou’s exhibition returns us to possible affectivity. Through a lyrical use of idioms and poetry accompanying tender renderings of various faces, we are brought into a different type of sensibility where we may find a new way of feeling, what I would like to propose we think of as deep feeling. Deep feeling as an embodied and affective type of feeling encountered only through conscious mental labour. In this instance, deep denotes what late American composer and member of Deep Listening Band Pauline Oliveros refers to as complexities, boundaries or edges beyond ordinary or habitual understandings. That which is deep as that which surpasses one’s present understanding or that which has too many unknown parts to grasp easily. By extension, deep feeling surpasses surface-level engagement of understanding another’s experiences. Deep feeling requires effort and calls upon us to dig deeper into our capacity to feel. As we look at the carved wood and the ink depicting the residents of Bilongue, we don’t claim to understand or know their experiences, we are simply pulling ourselves towards our full capacity to feel deeply with (not feel for) another.

Barthélémy Toguo’s Bilongue brings us right back to that quote from The Great Gatsby—for a transitory enchanted moment we hold out our breath in the presence of these images of the people of Bilongue, compelled into an aesthetic contemplation we do not understand, face to face with something commensurate to our capacity to feel.