Mous Lamrabat “Sir Mix A Lot” an online exhibition

Playfully presented on his Instagram bio, Mous Lamrabat lists three countries: “Belgium – Morocco – Mousganistan”. While the first two exist geographically on Earth and stake equal claim in the formation of Lamrabat’s identity, Mousganistan is somewhat new to both knowledge and vocabulary – and features as the artist’s wildly imaginative place of belonging.

“Mousganistan is a place I‘ve fantasised about since I was a kid. I never gave it a name back then, but it was a place where I felt I could be 100% myself.”

Born in Morocco and raised in Belgium; a self-taught photographer-cum-artist – Lamrabat’s is a tale of multiple identities, of many boxes – and, in turn, of the subversion and breaking-out of these boxes. Today Lamrabat’s vision, his place of belonging, comes to exist – like Belgium and Morocco – in the physical world as photographic series. It is the development of an archive of images that represent the specific vision of Lamrabat, spotlighting the world he sees, the world he lives in. And it is here, as images fictionally located in Mousganistan, that we find his latest body of work, Sir Mix A Lot.

Images with an accessible and axiomatic reference to art history, Sir Mix A Lot sees the deliberate interweaving of historically Eurocentric and globally contemporary aesthetics to playfully break with the traditions of the established, normative (art) world. Staying true to Lamrabat’s vision, the works featured in this exhibition discern the collision of multiple spheres – and we are presented with a body of photography that is only possible precisely because of its very unlikely – yet clearly coveted – intermingling of ambivalent iconography. Immerse yourself in Lamrabat’s subjects and their history, and you’ll quickly find that this is a body of work worth collecting.

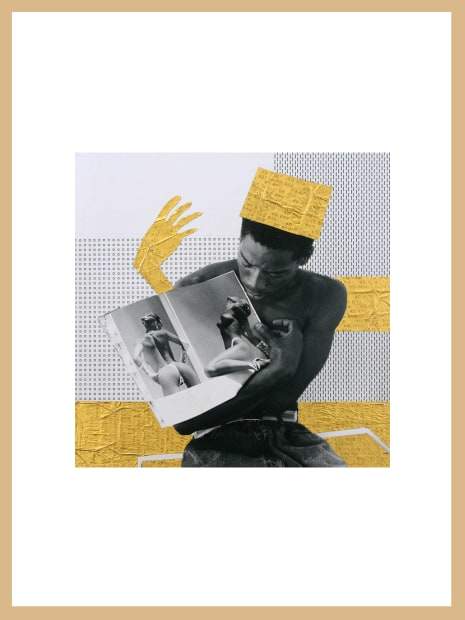

In the opening chapter to his seminal book, Ways of Seeing, John Berger writes briefly about the history and development of images – emphasising the important role of the image-maker in the visible: “…Later still the specific vision of the image-maker was also recognised as part of the record. An image became a record of how X had seen Y. This was the result of an increasing consciousness of individuality, accompanying an increasing awareness of history.

Berger continues: No other kind of relic or text from the past can offer such a direct testimony about the world which surrounded other people at other times. In this respect images are more precise and richer than literature. To say this is not to deny the expressive or imaginative quality of art, treating it as mere documentary evidence; the more imaginative the work, the more profoundly it allows us to share the artist’s experience of the visible. ” And it is in exactly this respect that we see the work in Sir Mix A Lot come to life.

150 x 100 cm

Click on the image to learn more

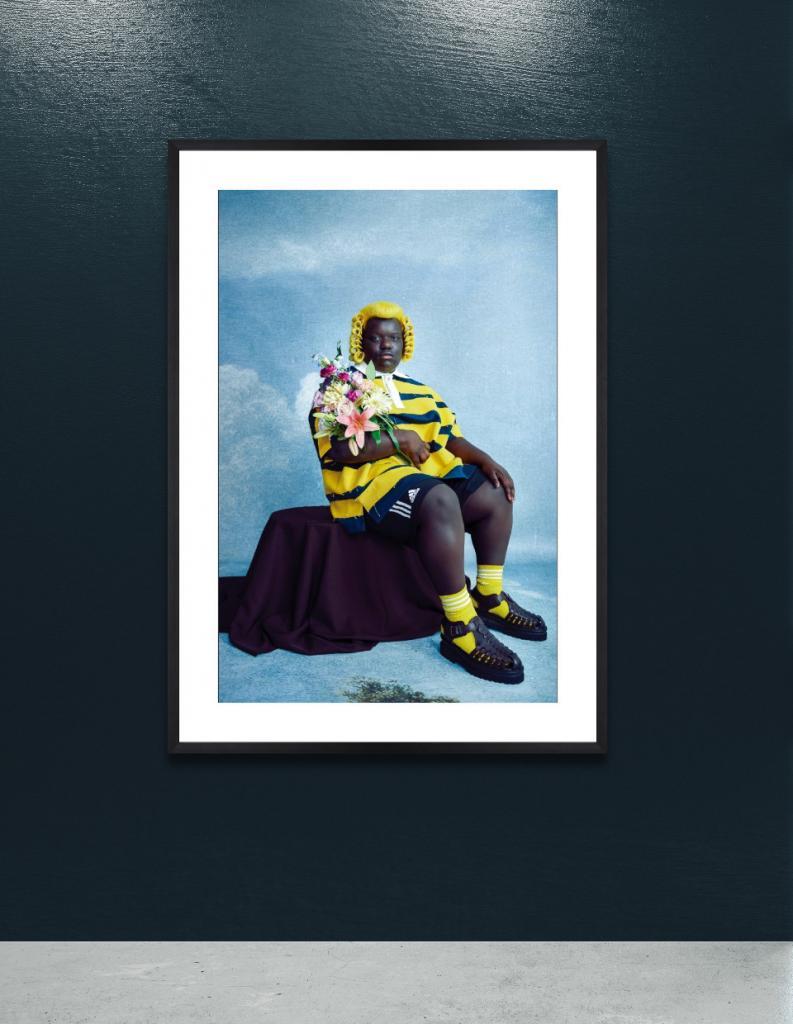

Here, in the artwork titled Brozart, for example, we see a subject dressed in Adidas sports fashion – arguably the contemporary world’s admission of rank; in stark contrast to this, he wears a dyed-yellow judges wig – an ancient symbol of aristocracy reflecting one’s elevated social status. Whilst the symbols featured here may mean the same thing – a declaration of class and standing – they’re from vastly different times, places and societies, and Lamrabat has reworked them to suit his narrative: in Mousganistan we’re all of this class.

Brozart’s subject is also seated upon a plinth draped in deep purple cloth; he bears a bouquet of flowers in one arm while the other rests lightly on his knee. The pose is symbolic of traditional portraiture; throughout art history we have seen powerful and upstanding individuals depicted in this manner – and it is perhaps here, too, that Lamrabat’s work finds its value. The limitless sky behind Lamrabat’s subject – which features in each portrait of Sir Mix A Lot – is a direct reference to the clouded sky in Belgian artist René Magritte’s The Son of Man (1964); yet here there is no skyline, these subjects will not be grounded.

150 x 100 cm

Click on the image to learn more

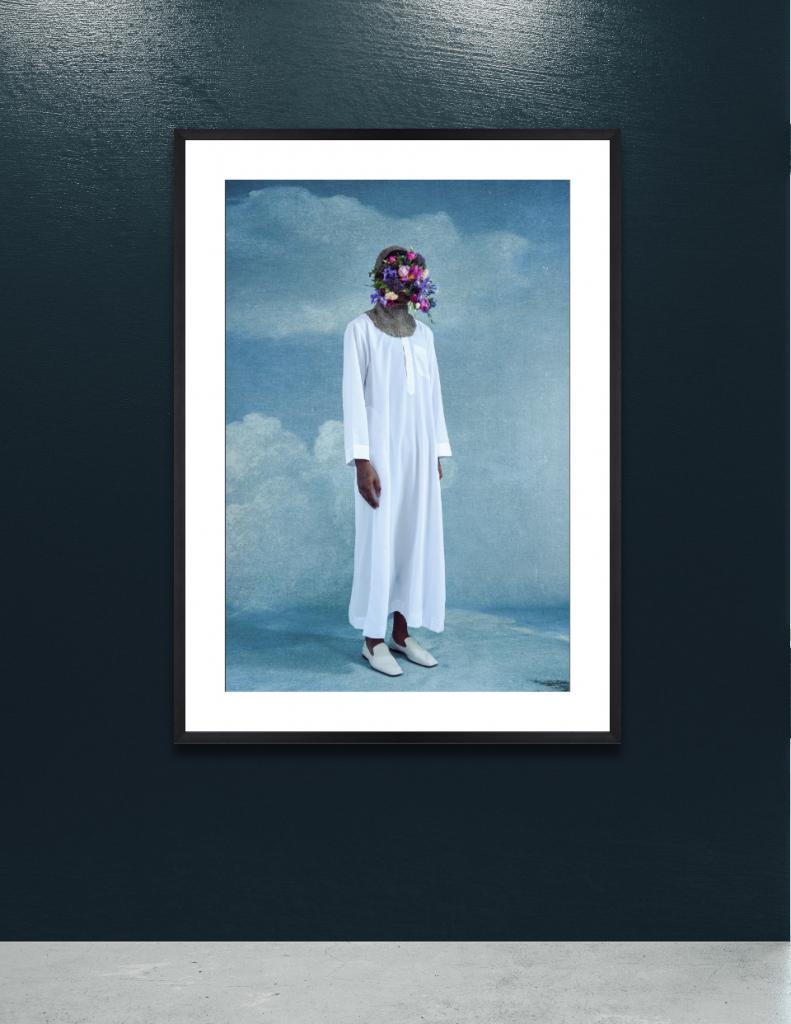

Following through with his reference and perhaps tribute to Magritte is Lamrabat’s Ceci n’est pas un Magritte (This is not a Magritte). An overt play on both Magritte’s The Son of Man and The Treachery of Images (1929) – Lamrabat’s subject stands facing the camera, his face distorted by an apple that has been taped over it – cheekily not unlike Maurizio Cattelan’s recent creation, Comedian (a fresh banana taped to the wall of a gallery booth at Art Basel Miami in 2019 – you’ll know it when you see it).

Almost indiscernible from the original artwork, Ceci n’est un Magritte breaks from The Son of Man only with the slight, creeping presence of a tattoo on the figure’s neck, and with the silver strip of duct tape holding the apple in place. And, this time, the subject is black.

“Museums were never places I went to – I just didn’t know this world. So I wanted to recreate this art form in a way that people, like me, would be more appealed to the artworks that hang inside galleries and museums. I just asked myself – why didn’t I enjoy these old paintings that cost a fortune? Why don’t they speak to me? What would speak to me? And then Sir Mix A Lot came to life.”

150 x 100 cm

Click on the image to learn more

A sort of anti-art series in celebration of those who have historically lived on the fringe, Sir Mix A Lot charmingly mimics the images we have seen so often in the world of art and turns them into images that Lamrabat – as well as a whole generation of immigrant youth – wants to see.

In Ways of Seeing, Berger also writes that “the majority take it as axiomatic that the museums are full of holy relics which refer to a mystery which excludes them: the mystery of unaccountable wealth. Or, to put this another way, they believe that original masterpieces belong to the preserve (both materially and spiritually) of the rich.” Lamrabat is not of this majority, however; his works belong to the preserve of Mousganistan’s rich: “I love to bring people to one status. No one too rich for my art, no one too poor!”

100 x 150 cm

Click on the image to learn more

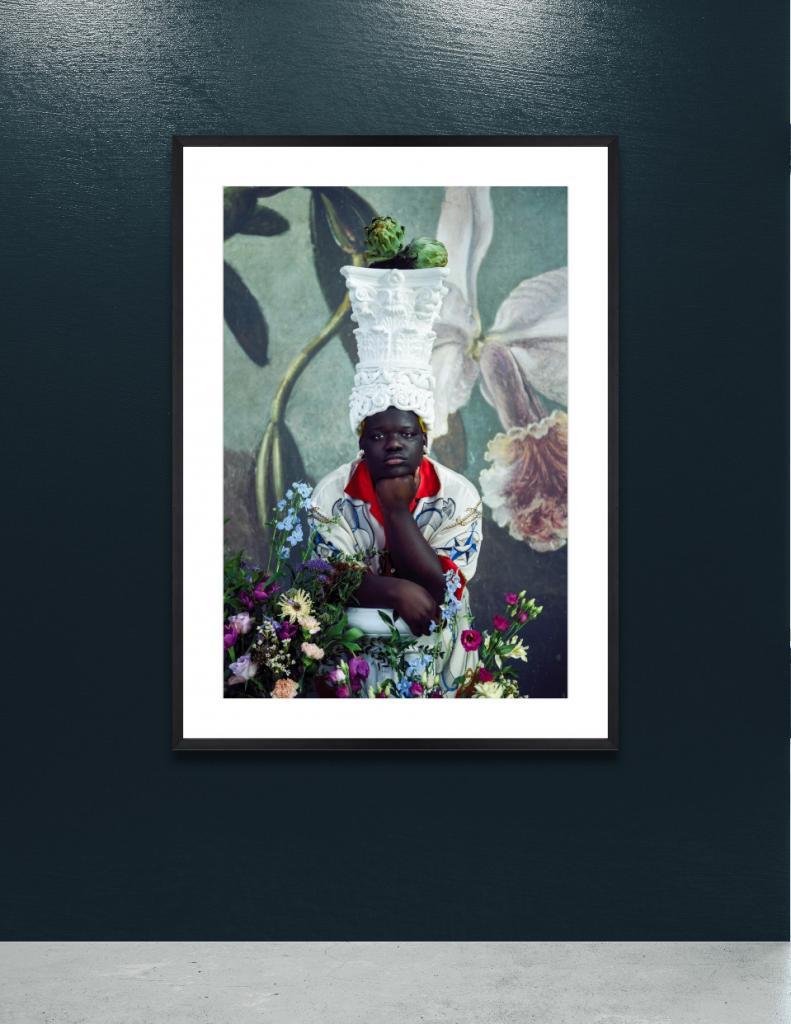

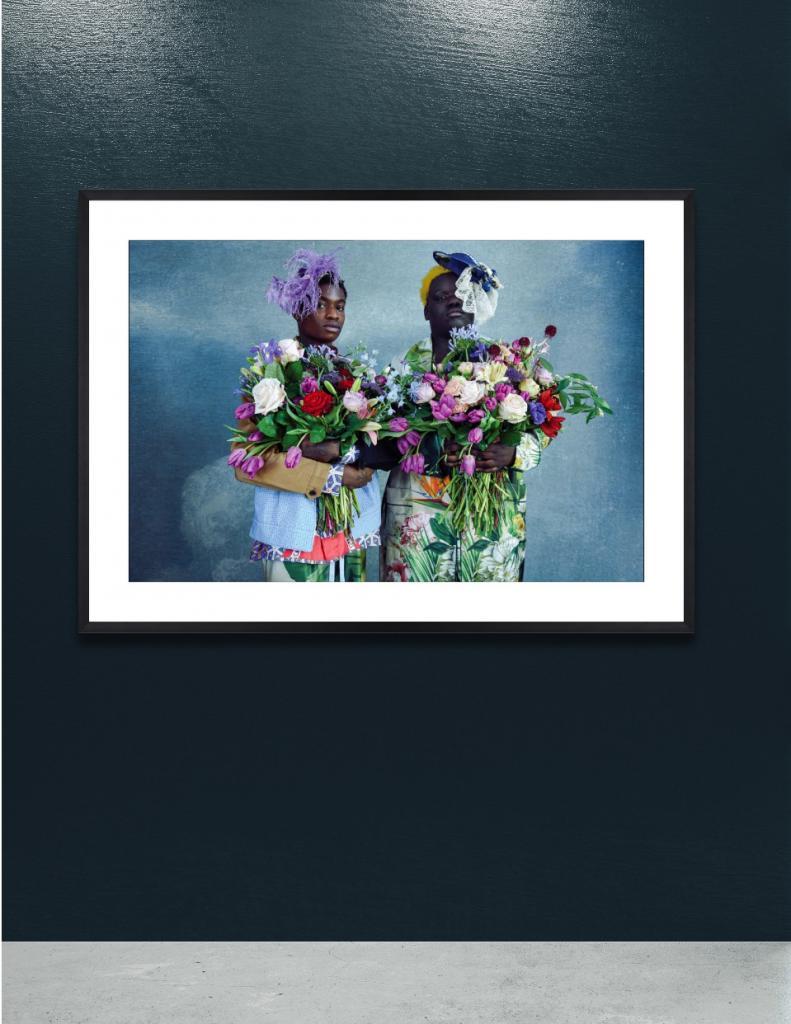

In his work Fresh from the garden of Compton, Lamrabat has dressed his seemingly masculine subjects in a very dandyish collection from Dolce & Gabbana – a purple, feathered hat; a navy titfer decorated with cream lace – while each figure holds a large bouquet of assorted flowers. Here, through the very infinite variety Lamrabat has presented us in disregarding male from female, we are presented with an image that makes impossible the emergence of any single meaning and view.

100 x 150 cm

Click on the image to learn more

Historically, in art, the representation of flora and foliage may refer to anything from religious symbolism, to reproduction, to decay – yet for Lamrabat, they are here simply because of the beautiful aesthetic they bring to an image.

“I’m a big flower fan myself, because they always give you a beautiful aesthetic. So sometimes I included them as a reference to paintings, and sometimes I just really liked them.”

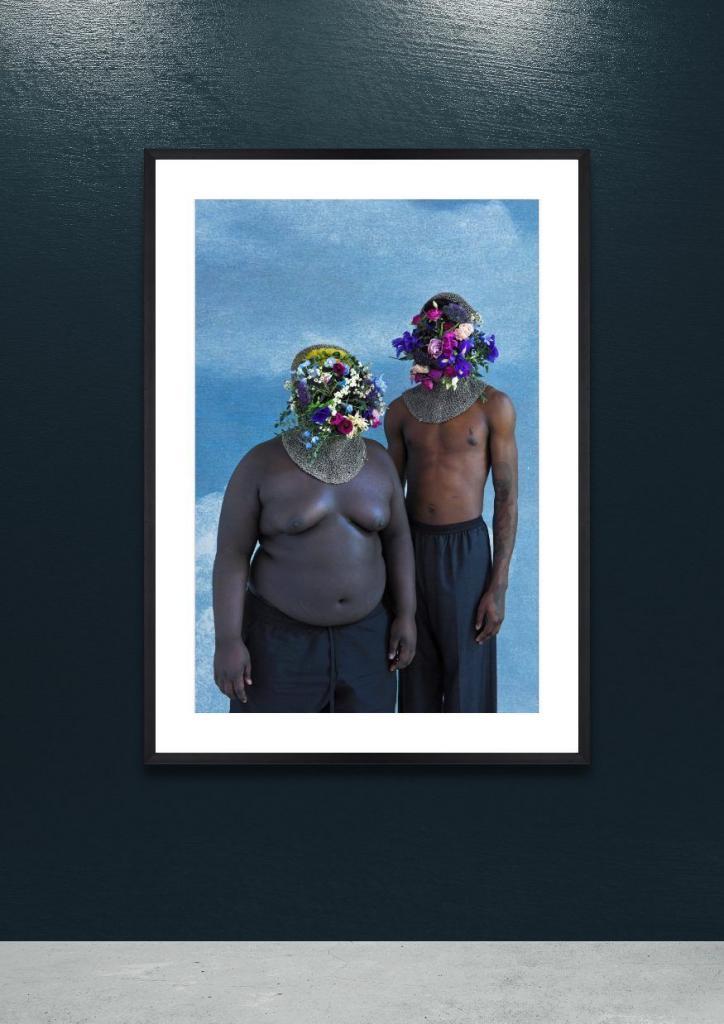

Natural Homies also sees two figures adorned with bouquets of flowers. Enmeshed in chainmail armour reminiscent of medieval armour, the flowers form a sort-of protective shield, a flower-mask, over Lamrabat’s subject’s faces while their chests and arms remain bare. They wear tracksuit pants pulled up to their waists. For Lamrabat, there is no specific reason for the iconography of this image, no particular agenda.

150 x 100 cm

Click on the image to learn more

“I remember thinking to make a flower mask. I never tried it to see how it would look, but on set we just tried it. I was so in love with it that I didn’t want any other garment in the picture. It was so pure and it became something poetic that I just made it about the flower-masks. I’m sure I can come up with something more sophisticated as an explanation, but if you want the truth, it was love at first sight. I had so much emotion… And emotion is something that I’m always looking for in my work.”

150 x 100 cm

Click on the image to learn more

The transparency and openness of Lamrabat’s images is infectious, and lends to their playful and whimsical quality – not to mention their value as a photographic archive.

Throughout Sir Mix A Lot, in its presentation of multiple spheres and infinite variety, of ambivalent iconography and axiomatic reference to art history, we have seen how images continue to conjure up the appearances of something that was absent, and how the specific vision of the image-maker remains an important testimony about the (real and imagined) world – “Belgium – Morocco – Mousganistan”– which surrounds us. In Lamrabat’s work, we are reminded: The more imaginative the work, the more profoundly it allows us to share the artist’s experience of the visible.