We’ve come to take you home

The University of Cape Town’s Works of Art Committee (WoAC) is currently hosting an exhibition titled We’ve come to take you home #1. The exhibition serves as a point of reflection, following the student protests that challenged the status quo of universities in South Africa, including challenging artistic representation and curation on campuses. It showcases some of the committee’s recently acquired artworks from 22 artists.

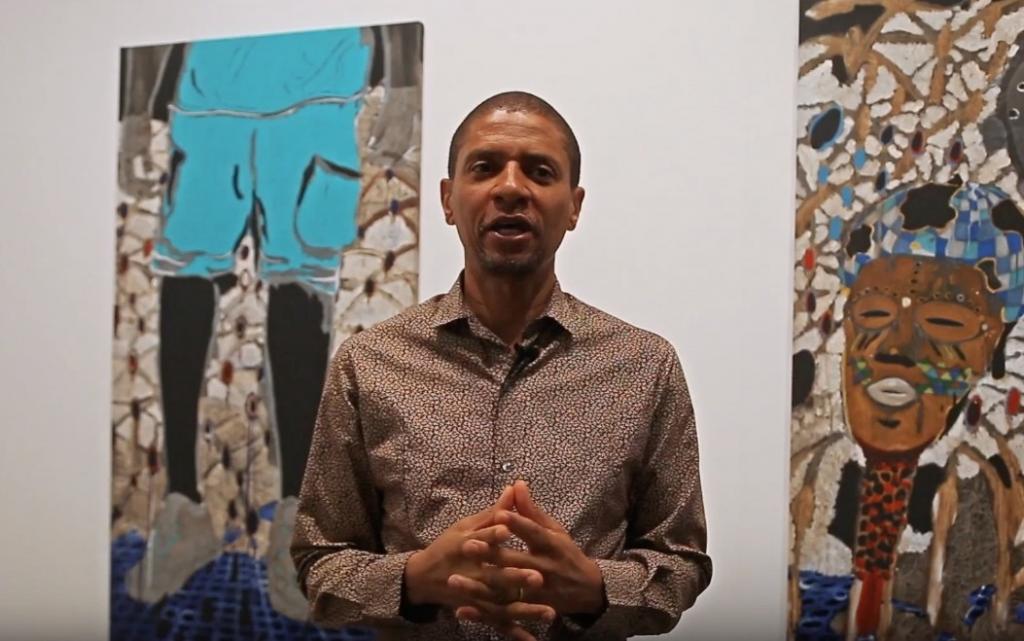

Artskop interviewed committee member of the WoAc and curator of the exhibition; Amogelang Maledu.

NM: Why is this a critical moment to reflect on collections and acquisitions, particularly at UCT? or rather, is there something about this moment right now that makes the reflection salient, pertinent?

AM: The Works of Art Committee (WOAC) at UCT under the leadership of Professor Jay Pather was instituted in 2016 following the torching of artworks on Upper Campus where students felt that the artworks curated on the campus’ buildings and hallways didn’t represent the demographics and diversity (both culturally and artistically) of the institution. This was known as Shackville, which was in conjunction with the Must Fall movement and the broader discussions around institutional racism and the critique thereof, specifically at UCT, but also broadly to institutions of higher learning in South Africa. These moments became fundamental in engaging the discourse of the institutions’ historical collection practises that seemingly didn’t change much despite the country’s transformation agendas post-1994. In 2016, a research task force team mandated by UCT management found that 79.1% of the artists in the collection were white artists. So the work of the committee, under Prof. Pather, and by extension, through the recently acquired artworks we’ve bought and some showcased in this show, is really interested in the reflections of those moments with a curatorial lens that is intrinsically cognisant of the historical and socio-political exclusion of non-white artists in cultural production.

NM: One could view the exhibition from a lens of “inclusion”; thinking of how Black artists are constantly being “included” into existing white supremacist, heteropatriarchal, capitalist structures as a way to show progress etc. If that is the case, what does this inclusion do to the decolonial process where these structures (e.g. the UCT art collection) are possibly upheld and not dismantled or undermined?

AM: In the curation of this exhibition, I am very careful to not frame the exhibition as decolonial because as far as my understanding of decolonisation goes, it isn’t. What WOAC does through these recently acquired works exhibited at Michaelis is deliberately respond to the visceral and legitimate charge students demanded during Shackville and the larger Fallism movement: UCT has been and continues to be challenged to be the African university it needs to be for one of its most important stakeholders; students. The status quo, and delayed transformative ideals that the institution supposedly espoused post 1994 are being perpetually challenged for their effectiveness in the contemporary. They will continue to be until the fruits of transformation are socio-politically, culturally and economically felt by those who form part of the institution’s fabric and that is a commitment that won’t simply take the inclusion of non-white artists into a collection to fully transform and become inclusive. It is a much bigger project that WOAC is not claiming to do on its own. More so, the socio-political angst of colonisation’s ramifications, as per the project of decolonisation, is not simply a UCT question alone, as the world is largely conceding with these questions of equity in general. These questions of decolonisation, transformation and re-thinking new justifiable societal models are conversations that continue to determine and inspire the production of art and culture and subsequently frame and gesture to how even UCT (through WOAC and prioritising specific artists in their collection) is itself grappling with these concerns, and by extension through the committee’s democratic nature, is interested in having an array of voices added onto the discussion of espousing the ideals of transforming the institution.

NM: Can you speak to me about the ideas of home in relation to the art world and in relation to the title of the exhibition? Where is home? Why home? Home for who?

AM: The title of the exhibition is intertextual and resonates on many levels with regards to ideas of home. The title is a direct reference from an acquisition WOAC made—an artwork by Lady Skollie titled WE HAVE COME TO TAKE YOU HOME (A DIANA FERRUS TRIBUTE) which is another intertextual reference to Diana Ferrus’ poem; I’ve Come To Take You Home, written in 1998 as a tribute to Sarah Baartman in anticipation of the return of her human remains from France to South Africa. Her human remains were on public display at the Musée de l’Homme up until 1974. The framing of the idea of a homecoming was important to me in thinking about the larger resonance of the movement of lives and objects in society and the impact those have in the contemporary. These movements are culturally significant especially if we situate the legacy of colonialism by looking at the story of Baartman and her subsequent objectification in a museum, a cultural and artistic space that is also largely responsible for the project of validating colonialism.

And because of South Africa’s historicity of exclusion as a result of colonialism and apartheid, the country and by extension UCT hasn’t been considered home for South Africa’s majority even after apartheid was abolished, former white spaces still feel exclusionary especially in a city like Cape Town. So curatorially it was important for me to reclaim the collection of UCT as a legitimate home for the artworks of artists that would most certainly be historically excluded in the past. WOAC and by extension UCT is in a capacity to intentionally create space for artworks by artists that would’ve and have been marginalised by systems of white supremacy that even implicates the collection itself.

NM: In curating the show, what would you say were the key threads (thematically, visually etc) that you were trying to uphold, especially when thinking about where to place works and how they converse with one another?

AM: The placing of each and every artwork was deliberate, not only from an aesthetic point of view but also from the subject matter of the artworks in relation to one another and spatially too in terms of curation. For instance, it was very important for audiences to be confronted first and foremost with Helen Sebidi and Buhlebezwe Siwani‘s work to speak to intergenerational conversations of Black women artists in South Africa and the marginalisation that continues to resonate even post-apartheid.

Regardless of how prolific of a career you have established, collections that should be prioritising your work, haven’t and it’s more than unfortunate—it was important to expose that incongruent gap that may have been a surprise for many.

UCT, since its collection in the 1920s, had not collected an important Black woman art historical figure that continues to inspire many other young Black women’s artistic practices today. It was very important to pair Sebidi with Siwani’s work, who through a collective she is a part of, iQhiya, challenged and resisted the marginalisation and systemic exclusion of Black womxn artist while studying at Michaelis School of Fine Art. That stark critique and reflection point for my curation and WOAC was important to illustrate how pervasive and relevant the question of inclusivity remains.

Many of the artworks in the exhibition are produced by recent UCT alumni. Even though through the committee’s acquisition mandate, prioritising artists that come from the university was not necessarily deliberate, it became important that we also support artists in their early careers.

NM: Are there some artworks that you specifically would have wanted to include in the show that did not make it?

AM: Yes, the show at Michaelis is only showing some recent acquisitions as there are many that couldn’t fit because of space constraints. That is the challenge again for WOAC; we don’t have a permeant museum or gallery to have long term exhibitions of our collection. So collating some of the artworks we’ve recently acquired and showcasing them in a thematic exhibition where their curation is intentional, is important in situating the larger conversation of why specific artworks were or are collected. After the exhibition, these artworks go back to being displayed in campus hallways, common areas and offices of various faculties of the university; thus not always being appreciated from a cultural and site-specific perspective – they can easily become decorative. However, we are planing more exhibitions; We’ve come to take you home #2 will follow at the Irma Stern Museum in March/April.

We’ve come to take you home #1 is on view at the Michaelis Galleries until 24 March 2020.