Lawrence Lemaoana: Threaded Histories, Textual Subversions

For the second interview of the series in partnership with 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, Christa Dee for Artskop3437 interviewed Lawrence Lemaoana. Lemaoana’s work has always offered prompts and provocations. The semantics and hidden scripts of political statements accompanied by the socio-historical threads that complicate the relationship between mass media and ‘the people’ are his exploratory thematic milieus. In this interview the artist shares more about his upbringing during the 80s in Apartheid South Africa, the connection between history, text and textiles and the layered references that influence his work.

Christa Dee: Your work unpacks and offers viewers a prompt to critically consider South African mass media and problematics related to its independence and the relationship established with ‘the people’. Could you please share more about this kind of uncovering and form of disenchantment present in your work?

Lawrence Lemaoana: I intuitively became aware of the political use of the term ‘the people’, ‘our people’ and ‘the masses’ as South Africa only gained democratic status in 1994. As a child of the 1980s I spent a portion of it in a small and ‘politically sheltered’ gold mining town of Welkom. As this was conceptually unbeknownst to me at the time, a period where Apartheid South Africa was waning in power over the lives of black people.

I did not know what state instituted segregation was, despite me only seeing white people on special occasions when we ventured into the ‘city’ and on television. I was furthermore clueless of what an Asian person looks like in real life as the province of the Free State banned their entering. In those days walls, as determined by the likes of Donald Trump, were purely conceptual but had the might of physical manifestations. My world was purely black to the point where even in plain speaking ‘human beings’ were SeSotho speaking people. The ideology of Apartheid corrupted the sense of self in relation to others by manufacturing a solipsistic definition of the term ‘the people’. The invisible bars over the mind were supplemented by an education system of Bantu education 1https://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/bantu-education-boycott, which determined that I as a child could only imagine my adult self as a hostel dwelling gold digging miner.

In his book Homo Sacer Giorgio Agamben’s interpretation of the people spoke of fixated station for so many in South Africa as “the poor, the disinherited and the excluded”. The contemporary use of the term has become “the previously disadvantaged” who were the bodies to maim and shoot at in marches and protests in Apartheid South Africa.

Sloganeering became a useful way of fueling protest marches; I grew up on a staple diet of the Nguni phrase Amandla! (The power) being dished out on the crowds. The crowd would in turn burp out Awethu! (Is ours) while carrying often misspelled placards determined to say “Power to The People” (2008). Supplementary support to this process was the creation of posters. The Medu Art Ensemble was a group of ‘cultural workers’ who were exile in neighboring Botswana, produced posters through creative workshops and discussions program. Their later released book and catalogue of their work influenced my thoughts.

On the other hand, the post-apartheid condition of most black South Africans or the so called ‘people’ has been one filled with hollow promises. Because of very little fundamental and infrastructural changes in this society, the post-apartheid epoch is infused with disappointment. The media in the form of Naspers, currently renamed Media 24, exemplify the cosmetic changes. The company has apologized for aiding apartheid ideology.

South Africa experienced a publicized identity as the ‘rainbow nation’ during Nelson Mandela’s term, as the first black democratically elected president. Rose tinted glasses can only describe the writing in newspapers. To which I use this analogy of how pain killer work, it is simply a blocking of messages that alert the brain of the wound, the wound remains there despite this blinding scenario. The reality is that the people are wounded and healing has not been made priority in real or material terms.

Your use of the Kanga cloth and the words and phrases woven on to the fabric makes your work highly localised on one level, referencing South African socio-political circumstances. At the same time, the Kanga cloth through its own historical journey (its production in the East and how it is sold in South Africa, and it subsequent absorption into important spiritual attire) pulls into your work an awareness of South Africa’s placement within the global economic chain. Please share more about this layering of references in your work, and how your thinking around it has evolved with your practice over the years?

In terms of religious practice, South Africans stands at 86% of the population identifying as Christian. This fact seems to be functional in politics. I often begin processing my ideas with the biblical concept of the “word”, pointedly on the phrase “in the beginning was the word”, to which I add, and the word became text.

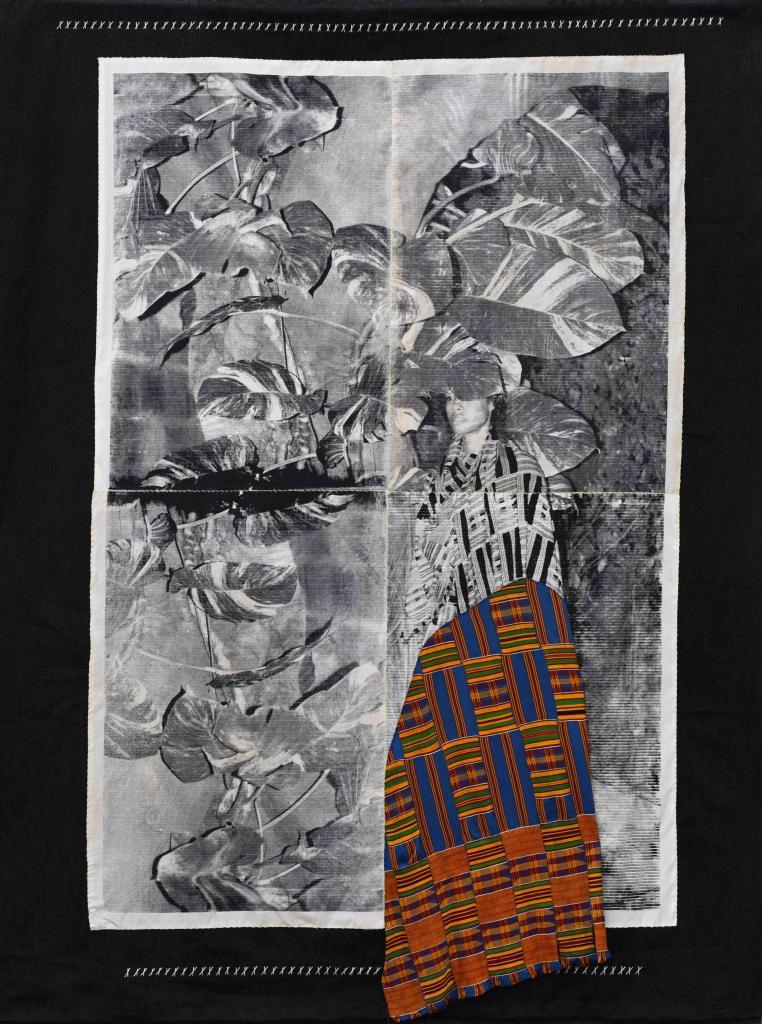

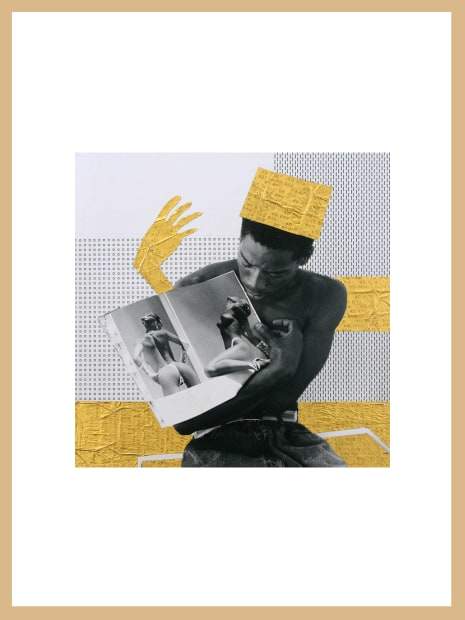

In the journey of my research, I also stumbled upon the link between text and textile, which is that they both mean to weave. This kind of story telling comes into play in a work I titled ‘I put a spell on you’ (2019), which I considered the idea of reading text as a form of spell binding. I was also acknowledging with respect Screaming Jay Hawkins and Nina Simone. Their deliveries of the same song speak to a kind of spirituality. The political link in the work is asserted by the black, yellow and green of the ruling African National Congress (ANC). The color scheme alluded to the liberated black people, the minerals or gold that those masses are entitled to and the green the land that would institute dignity for them. The visual complexity feels heavy as I consider an open audience that would either be lost or find solace in the work. The references stem from politics, theological considerations, visual metaphors, etc.

The kanga as an African fabric became an object of interest when the former deputy president of the ANC was tried in court for rape. In the heat of questioning, the accused indicated that he understood his sexual advances to the woman young enough to be his daughter as consensual since she wore a kanga.

Further reading indicated that in east Africa kangas are used for many purposes, including as communication device. The kanga has decorative patterns and motifs. It usually has a text that functions as an idiom. The idioms are constantly changing and owe their being contemporary lingua franca and fashionable phrases. The textile companies have been known to scout for these phrases and in a way produce an ecological niche for the circulation of their product. By design the idioms are accompanied by illustrations.

In all these processes of repurposing, I am brought back to the artistic term appropriation. New life is breathed into an object that is taken out of its ‘natural context’ of circulation, new meanings and metaphors are produced when their function as garment, as a cultural and spiritual object. Purchasing the kanga, augmenting it through embroidery and patchwork, placing it in a gallery space or a museum redefines its parameters as a communication device.

How do you think the transference of oral or written political statements on to cloth in your work shifts and/or directs the way in which these statements are read, processed or revisited?

Commemorative kangas were produced as early as the 1930s, where an individual’s image was printed on the textile, and patterns relating to who they are decorated the rest of the fabric. As an artist, I attempt to subvert and work with inherent qualities of the objects, meaning that tracking down the history and use of the textile informs my thinking about it. I take cognizance of text-based artworks by artists such as Glenn Ligon, Pope.L and Dread Scott to name a few. I think that these artists’ works place the meaning of words constructively under stress, challenging ordinary uses.

One of the supporters of the liberation of South Africa from apartheid was the USSR. To this the political culture of South Africa was contaminated. The colour scheme black, red and white that I use in my work references Russian propaganda posters, while at the same time referencing the spiritual colour scheme of Sub-Saharan Africa. My interest comes in transforming the reading of the texts into ambiguous objects that lose functionality but gain new powers. I try to reflect a distilled sense of my contemporary world by unearthing quotes that may spur individuals to actors.

A work titled ‘Things Fall Apart’ (2008) was a response to the political turmoil in my country in the 2000s. I lifted the title from Chinua Achebe’s 1958 novel. The title was a line taken from a poem The Second Coming by William Butler Yeats. These different forms of writing speak to an interdependence between ideas from different creative zones. My probe is one of a rhetorical question ‘Can an African artist produce conceptual none figurative art?

Your work also offers contemplations on the constructed nature of identity, and the material reality that is attached to specific categories of identification. Please share more about this thematic interest?

I believe artworks are a fragment of the artist’s ego. Experiences, sound clips, gifs inform and misinform the work. I paid attention to the children’s movie Jungle Book particularly Louis Prima and Phil Harris’ – I Wan’na Be Like You (1971) song after reading through Paulo Freire’s book The Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Another work that shook me was Cildo Mereiles’ Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project 1970. The work that emanated from these critical engagements was ‘Lay the secret on me of mans red fire’ (2015). I was intrigued by the envy of the orangutan who had ambitions to be a man. This envy was reminiscent of Franz Fanons assertion that “The colonized man is an envious man”. To a more local example, the idea of liberation in my country meant occupying previously illegal positions in our society. The product of this was a sitcom titled Suburban Bliss, which in a nutshell was about a black family moving into a former whites only suburb. All of these cultural productions weave strong narratives about identity.

What do you think a presence at 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair presents in relation to debates around the representation of African artists within the larger art ecosystem?

Speaking from a personal experience, the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair rescued me from a slump of despondency. The despondency was due to my critical outlook and complicit participation in an art system the seems to have preconceived ideas about what African artists should be producing. I think that the fair opens up a safe space to be explorative and indeed innovative in how to read and make art for Africans. I think in this way African artists have the opportunity to be artists as opposed to ‘performing as specifically African artists’. I think that the anthropological term ‘native informant’ becomes useful here in that in the general art world African artists are often tasked with continually explaining themselves and their biographies often placed paralleled with their work.

In similar fashion to the feminists and people of color (the Other) of the 1960’s in the West, who entered museums not in the way that they were previously represented, but by speaking authentically of themselves through their work. In those processes presented expanded concerns and interests in their art making. In a nutshell their mediums are imbue their messages. I find it impressive that 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair creates a similar and equally important task today.