Alpha Crucis – Contemporary African Art, the end of a monumental series of exhibitions

Alpha Crucis – Contemporary African Art concludes a series of exhibitions launched in 2005 that have used geography as an organising principle to curate contemporary art. While hardly revolutionary in approach, the challenge with this final exhibition is that where previous instalments such as Brazil (2013-14) or China (2017) represented countries that are culturally complex, none were quite as vast as the continent of Africa. The exhibition’s guest curator André Magnin, a contributor to one of the first art exhibitions credited with disrupting Eurocentric aesthetic values – Magiciens de la Terre at Centre Pompidou and Grande Halle de la Villette in Paris in 1989 – culled for this exhibition seventeen artists from seven countries representing sub-Saharan Africa.

While conventional in its display, practices only recently welcomed into the hallowed halls of contemporary art feature prominently: textiles in particular. Viewers initially experience Malawi-born, South Africa-based artist Billie Zangewa’s pieced and sewn works in raw silk from a distance. Stepping down from the ticket area towards Zangewa’s work creates an optical game that makes her choice of materials a surprise not necessarily visible from a distance. Zangewa describes The Rebirth of the Black Venus (2010) towering over downtown Johannesburg as biographical; the title also suggests the historical figure of Saartjie Baartman, whose body in the early 1800s infamously became the subject of colonial prurience – only eventually returning to South Africa for burial in 2002. This tension between the personal and the political perhaps troubles art from the African continent more so than elsewhere.

If an ability to recognise political subtexts feels almost mandatory interpretation for the diligent viewer, Zangewa’s figure wears a banner announcing a useful mantra: “Surrender wholeheartedly to your complexity”. The phrase could be carried throughout the exhibition, which makes no curatorial claims of thematic cohesion. Where Zangewa uses textiles to create works that may look like paintings from a distance, the patterned paintings of Malian artist Amadou Sanogo recall textile patterns without the literal use of cloth. Instead, Sanogo’s paintings are informed by personal knowledge and experience, in his case of the labour intensive textile dye process of bogolan. The technique uses fermented mud on cotton to pattern woven textiles often with a high contrast palette – an aesthetic that carries over to Sanogo’s stunning paintings.

In the upper mezzanine two South African artists use stitch for very different aesthetic means. Senzeni Marasela’s ongoing work with textile and performance is inspired by her mother’s generation, life under apartheid and the women who wait because of work, or war or incarceration, for their men. In the ongoing series Waiting for Gebane, delicate red water colours and stitched thread line drawings evoke the erasure and disregard for women’s identity. The artist uses the derogatory description “Kaffir sheet” to describe the material she stitches into – a re-appropriation of the name denoting coarse quality cotton textiles sold during the colonial era in rural trading stories of KwaZulu Natal and the Eastern Cape.

Nearby, Nicholas Hlobo’s trademark use of recycled rubber tyres and vibrant organza stitched with ribbon sutures create a sculpture that is both phallic and anthropomorphic – a reference, at least in part, to the artist’s identity as openly gay black South African man. The museum’s online podcast explains Hlobo’s use of his native language of Xhosa for titles (which remain untranslated) in the sculpture Ndimnandi ndindodwa (2008) and stitched wall piece Nalo ikhwezi alinyulu (2015) as a “reference both to his own roots and how art often needs to be translated when seen outside of its original context”.

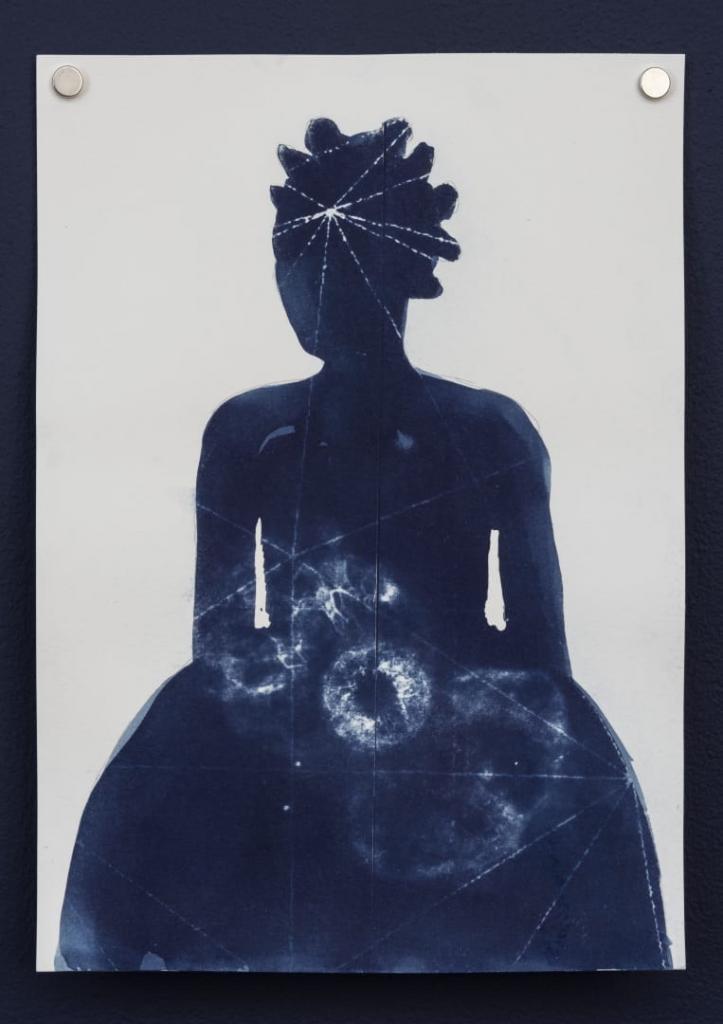

If Zangewa’s The Rebirth of the Black Venus towers over the urban horizon of Johannesburg, Wura-Natasha Ogunji’s Atlantic (2017) offers another image of female empowerment. Ogunji works across media, including performance, but here uses delicate tracing paper. A simple line drawn face carries a dense wrap of hair piled high supporting a turn table. Handwritten text trumpets from the subject’s ear: “We originate in loss. Our lost ones line the sea. We need to get back to them – become amphibious mammals like polar bears and platypuses. Our land aint Africa but the sand that is our ancestors bones.” Nearby haunting blue lines in The proof, an undersea volcano, attraction, extraction, distraction (2017) suggest faint veins outlining horizontal figures – a reminder of the catastrophic loss of life created by the transatlantic trade of enslaved Africans.

An extensive exhibition catalogue, printed with seventeen different covers, deserves credit for largely avoiding the trap of commissioning European voices to speak on behalf of the continent’s experiences. Babacar Mbaye Diop of Senegal contributes a useful overview of sub-Saharan contemporary art events, while “Notes Towards a Lexicon of Art and Place” written by Cape Town-based Sean O’Toole provides an insightful challenge to the exhibition’s somewhat unwieldly curatorial premise.

The two parts of the exhibition title deserve their own critique. Alpha Crucis is considered the brightest star in the Southern hemisphere. Invisible from the Northern Hemisphere, it is part of the Southern Cross constellation and – from Oslo, or anywhere in Europe – requires a physical reorientation to witness in person. Contemporary African Art in its vastness is an even trickier nomenclature. Hardly invisible to the northern hemisphere, the selected artists, for the most part, represent well established identities in a global art market hardly invisible to the northern hemisphere. In this aspect Alpha Crucis (curated in a pre-Covid world, of course) feels a little out of touch.