In Conversation With Visual Artist Shiraz Bayjoo And Curator Ilaria Conti

© Fondation H

Fondation H presents Shiraz Bayjoo’s first institutional exhibition in France, Lo Sa La Ter Ruz [On This Red Earth], curated by Ilaria Conti.

Expanding on the artist’s research into the colonial histories linking his native Mauritius to surrounding territories such as Madagascar, the exhibition presents a new series of works created specifically for the exhibition and highlighting the complex socio-political entanglements that have shaped the Indian Ocean. Presented on both levels of the Fondation H – Paris, Lo Sa La Ter Ruz is a critical reflection and homage to the resilient genealogies that have structured communities and transmitted knowledge through generations of colonised people, despite the crimes against humanity and nature they have faced.

Drawing on Bayjoo’s extensive research in French archives, the works in the exhibition propose new conceptual and material strategies of knowledge production, challenging the principle of extraction at work in colonial archives. I had the chance to talk with Shiraz Bayjoo and Ilaria Conti about some of the many aspects of the exhibition. I wanted to comprehend the challenges of Shiraz’s artistic practice and how they worked together with Ilaria Conti to put this exhibition together.

Politique des Races 4, Acrylic and resin on wood, 18 x 15 x 1.5 cm each

Politique des Races 4, Acrylic and resin on wood, 18 x 15 x 1.5 cm each

What does the use of colonial archives represent in today’s reflections on decolonial practices and more specifically in your work Shiraz Bayjoo ?

Ilaria Conti (I.C): Colonial archives are a very intricate subject of study and debate; they are sets of information shaped by truly complex histories. We must also understand how such information informs us: our knowledge, present-day processes, and ways of thinking. Much work has been done on the use and detournement of colonial archives, and it is important to continue to develop work that fosters awareness on the genealogies of these materials and the structures of power that these documents reproduce in the present.

We have long discussed with Shiraz the impossibility of having a one-dimension approach to archival materials, because they are in constant flux as much as we are in flux. Our ability to read and address them changes over time. We must therefore develop new thinking tools and a different vocabulary, as the relevance of these archives is given by those who look at them today, it is not just about the histories that someone collected in the past.

It’s crucial to think about how the activation of such archives through the histories they perpetuate in the present and their implications for the future. Addressing colonial archives is also brave, as these represent a slippery territory: they are ever shifting, and so are we in relation to them. This courageous line of critical thinking is central to Shiraz’s practice.

Shiraz Bayjoo (S.B): Colonial archives present multiple possibilities in unpacking the construction of post-colony national narratives, and ultimately the space in which we arrive at today. They become an important tool if we want to expand our understanding of our recent historical past. This work is about how histories have been recorded and how and where aspects of our identities and cultures have been collected, how they have been collected and how they are represented in the language of museums and museology. It is a complex journey in the re-representation of these materials, one that requires questioning and criticality in all directions around the subject, and throughout the process. It can become an act of reclaiming, making visible, and in this way pushing back against erasure. How ever we have to tread carefully, avoiding recreating the violence of the past, or the framing of language that has been used to obscure and ultimately reduce identities, cultures, and people.

Exhibition of Shiraz Bayjoo Lo Sa La Ter Ruz. Installation views. Courtesy Shiraz Bayjoo and Fondation H

Boneyard (détail), Panama tissé, encre à sublimation, Sapele, laiton, 100 x 100 cm

Can revisiting colonial archives today be considered in itself a form of violence?

S.B: It is important that we don’t enter into the replication of violence or its visual repetition, but we also don’t want to deny what has taken place. It is important not to thin our understanding of the depths of subjugation, and how people were forced to exist in a very specific way at odds with their traditional ways of life. Looking at the framework of language can be a useful way, without having to point directly to situations of violence. I think it is important to represent the depth of trauma, but with pathways that seek to serve the healing process.

I.C: It is a continuous and very delicate process of figuring out how to relate to these materials. In focusing on what is considered violent in such archives, we must learn how to engage with it and understand how to not reproduce such violence. It is not just a matter of acknowledging what has happened historically, but also to understand what was considered worthy of being part of such archives, and—as Shiraz has mentioned—who has access to them now and why. The revisitation of the archives is not a form of violence per se, but it certainly requires us to learn how to navigate multiple levels of violence. As we work through these materials, we also discover new, more subtle forms of violence that pertain to the present-day discourse and to our positionality as those who engage with such materials in the now.

Shiraz, why is it important for you not to restrict your research to the Mauritian case but to extend it to the whole Indian Ocean region? More precisely to the Great Red Earth? Is there a link here with the archipelago thinking of Edouard Glissant; act in your place and think with the world?

S.B: The research for this exhibition comes from a previous exhibition and body of work entitled Searching for Libertalia. It is a work that explores the process of African decolonization, specifically the process towards independence. Mauritius is central to much of my work not for patrimonial nostalgia, but because island post-colonies make visible the layers of the colonial project, of the hierarchies of race and people.

Mauritius is a colonial construct. For me it is important to situate it in relation to the wider region. Madagascar in contrast is claimed as a site of indigeneity, it is not a colonial construction, and can therefore reveal deeper layers. These are not historical projects, instead we explore our contemporary presence, unpacking language, and the framing of identity through Eurocentric visions. We have to be able to see beyond one space and understand particularly in the archipelago the interconnectedness of people and places.

Ilaria, in the paragraph 4 of the curatorial text it is said « Territory requires that filiation be planted and legitimated. Territory is defined by its limits, and they must be expanded. A land henceforth has no limits. » Can you please elaborate on what you mean by that? What do you think is the difference between land and territory ?

I.C: This quote by Edouard Glissant is one tool among the many he has developed to address the complexity of colonial histories. When considering Shiraz’s work and in thinking about the curatorial path of Lo Sa La Ter Ruz, land represents a central point. With Shiraz we had in-depth conversations about the possibilities of representation when working with archives, and we realized the strong focus that there is on the human figure. It was key for us to move beyond this exclusive focus and consider the intimate relations that historically have been established with the land. The aim is to place the human and the non-human on the same level and explore the deep interconnection that exists among these two dimensions. This is also why in the curatorial text we address genocide and ecocide as one deeply entwined element.

The works in the exhibition point toward the importance of thinking about the land as a place of knowledge and of its transmission—as well as of safety and refuge, as in the maroon forest featured in the textile work titled Riverstone. There is a crucial shift that takes place when thinking about land as a space of self-determination, culture, knowledge, resilience, and survival, as opposed to land as a site of extraction and exploitation.

The words by Glissant exemplify such shift, which leads to understand land as an entity with its own standing in society. I have therefore included this quote in the curatorial text as it insightfully mirrors Shiraz’s thinking and ongoing process. In this sense, the overall ecology of the exhibition can be seen as an ecosystem of interrelated elements that does not form a monolithic statement: it is a process that is not over yet, a point on a potentially endless arc of research.

© Fondation H

Precisely, in the Coral Island series, Shiraz, you reveal scenes that would be almost laughable if the matter wasn’t so dramatic: settlers having fun with the local fauna and taking possession of it, just as they did with the human populations of these islands. One can see the Dodo, an endemic animal of Mauritius, now extinct, as well as the giant turtle, also exterminated from the island but reintroduced thanks to the neighbouring species from the Seychelles archipelago: the Aldabra turtle.

S.B: Our relationship to ownership of land and the idea of extraction has a firm connection, exploitation of people through forced labour grew exponentially with the exploitation of natural resources across the globe throughout the colonial period. In the case of the Mascarene Islands, although there are no indigenous people, the ecology is of course indigenous. It is the fauna and flora that have witnessed the erasure more than anything else. Both become a metaphor in terms of reflection. It is a way to understand the violence, the backdrop against which all is unravelled. The plantation landscape, and the idea we are continuing the economics of the plantation, the Plantationoscene as a theoretical space opposing the position of the Anthropocene. It is upon this premise that we are still living in the legacy of this relationship of extraction, forced habitation, forced labour, forced productivity of human, animal, and plant. In fact, it is not just the colonial paradigm, but the genesis of the globalised relationship in which we live today.

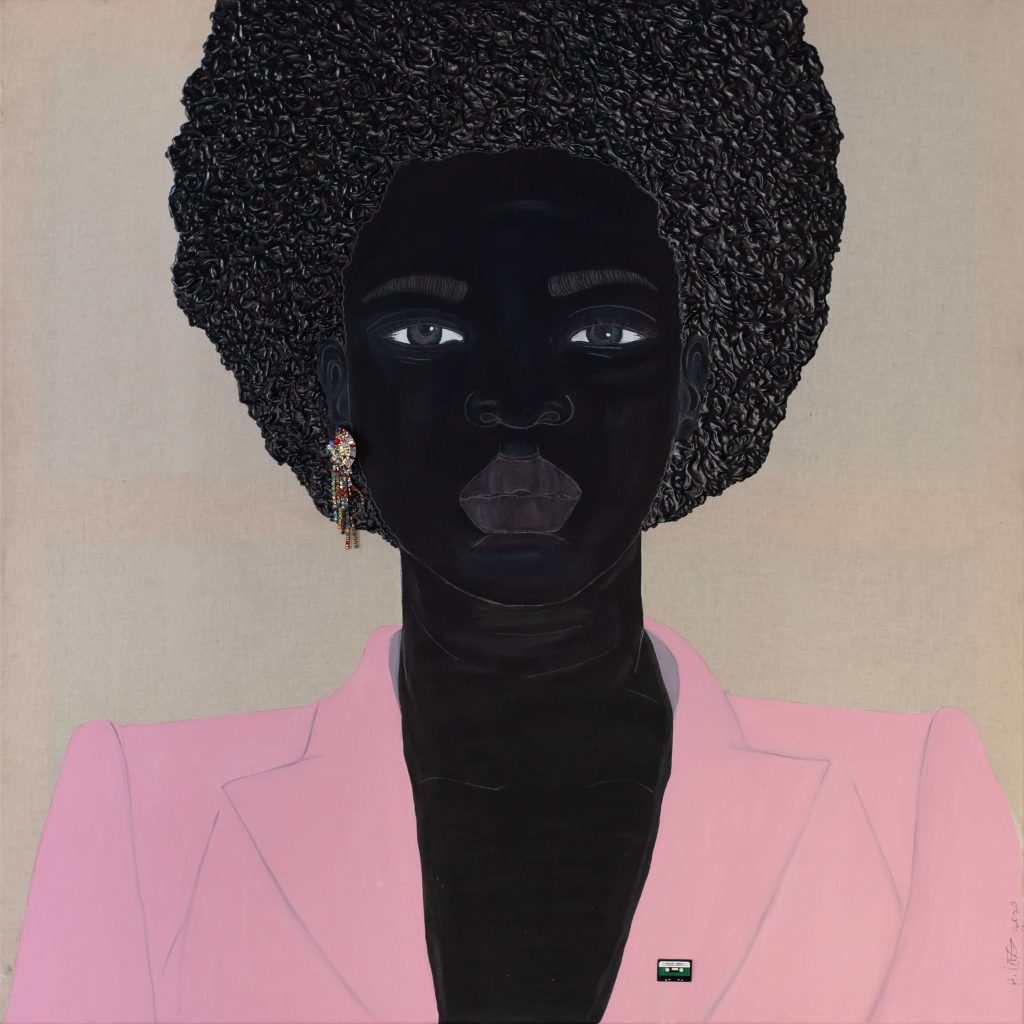

The work ‘San Visyon’ I quote the curatorial text “form a ‘material index of resistance'”. We also see in the series of paintings ‘En Cours’ drawn from the archives of the Musée du Quai Branly from which you creates new images that offer, and I quote, “an alternative and provocative archaeology. He brings to light the sovereignty of representation that the colonial archives have historically erased by their “order of perception”. I wonder about the links between the creation of a new imaginary and resistance in your work. Can you tell me more about this?

S.B: One of the very strong narratives that we have in Mauritius is the story of the maroon, of maronnage and the act of escape. How do you survive in situations of extreme subjugation? How does that inherited legacy prevent you from moving forward or being able to create a new sense of yourself? Perhaps the act of escape as recounted in the book ‘The old man and the Mastiff’ by the Martinician writer Patrick Chamoiseau provides a pathway; the language of resistance, of the survivor. Can we learn from indigenous communities, understand better the custodianship of knowledge, of stories? What are our stories of heroism, of survivors? We know for sure the great grandmothers who survived the plantation, so we exist today to reflect on their stories. Their survival strategies are a common thread between people throughout the history of slavery. Perhaps within this is the language to continue this process of decolonisation.

© Fondation H

Chi Lakaz 1, Sambo series, Sapele, archival print, map, coral stone, 77.5 x 30 x 25 cm

Shiraz, in reference to the ‘Sambo Sculptural Series’, can you tell me how does spirituality operate – has operated – as a means of resistance through everyday objects?

S.B: The Sambo Sculptures are offerings, intimate objects that would probably have little value in other spaces. However, in this context, they represent hopes, prayers, wishes and perhaps even spells. This series of works reflects upon the limits of our agency; objects and talismans become important tools in projecting yourself where none is possible. I think we have that in us as human beings. These objects and practices emerge from highly oppressive environments. We cannot underestimate the psychological power imbued upon these objects. This is why I come back to these spaces, offerings, that continue to exist today in Madagascar, Mauritius and around the world. These are survival strategies in secrecy and subtlety.

The exhibition ‘Lo Sa La Ter Ruz’ [On This Red Land] because it is, and I quote the curatorial text, “conceived as a polyphony of artworks that resonate with one another to convey and honor the complex experience of the colonized,” seems to highlight both the singularities and multiplicities of Mauritians and Malagasies with respect to the common colonial history. This is particularly evident in the work ‘Politique des Races (4)’, 2021. The elements remain distinct without denaturing each other while producing a new connected synthesis in motion and not fixed? This seems to echo the glissantian thought on creolization. The question is: Change without denaturing?

I.C: In this series Shiraz addresses the artifice that placing the human above everything else enforces. He decides to think visually otherwise, working with diverse small elements and creating new adjacencies among them so as to form new meaning.

This strategy can be seen as relating to notions of opacity, as the works seem to question whether it is possible to focus on a single, crystallized image that define nature in a singular, definitive way. In such process, an essential component is his process of “thinking through making”: the artist includes so many layers in his paintings that the potential meanings, atmospheres, and connections are always in flux; they form somehow a type of archipelagic thinking.

Politique des Races (4) moves away from the idea of “nature” as a single identity and from the essentialism that standardized images of nature carry within themselves. The series liberates the potential for such imagery to re-exist in the present, shaping new meaning that are radical and critical in their ambiguous and transient nature.