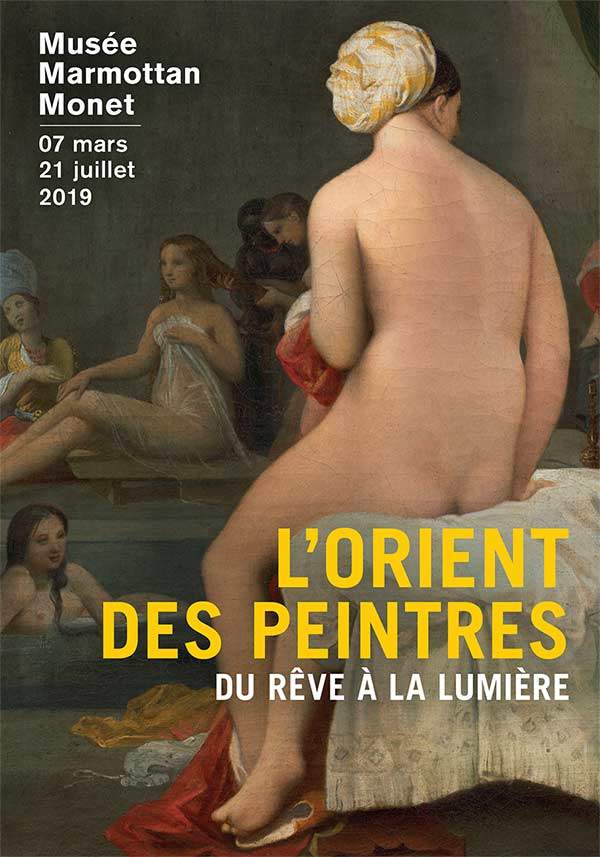

“Oriental Visions, from Dreams into Light” at the Marmottan Monet Museum in Paris

07/03/2019 - 21/07/2019With some sixty masterpieces from the most important public and private collections in Europe and the United States, the exhibition “Oriental Visions, from Dreams into Light”aims to reveal a new perspective on Orientalist painting through the journey.

It is in the private mansion that houses Paul Marmottan’s collections, dedicated to Napoleon and his family, that the exhibition takes place. It is indeed the breath of Napoleonic conquests that leads the painters to leave and to verify their fantasy of the Orient through the journey. The dawn of the industrial era thus gave birth to orientalism, which spans the entire century and European countries. At the beginning of the 20th century, the avant-gardes themselves were nourished by these new experiences and invented a new art, at the gateway to abstraction, carried by the East.

Bourg-en Bresse, Museum of the Royal Monastery of Brou © Carine Monfray, Photographer, Collection of the Museum of the Royal Monastery of Brou.

Faced with the many previous studies and exhibitions, the route favours the Mediterranean East, specific to the French colonial empire. The corpus of works has been organized into two distinct axes: the human figure and the landscape. Two routes announced by “La Petite Baigneuse” (1828, Paris, Louvre Museum) by Ingres and “Innenarchitektur” (Interior Architecture, 1914, Wuppertal, Von der Heydt Museum) by Paul Klee.

Oil on canvas – 35 x 27 cm – Paris, Louvre Museum, Paintings Department, acquired by public sale on the arrears of the Poirson legacy, 1908 – Photo© RMN-Grand Palais (Louvre Museum) / Michel Urtado

These two lines illuminate each other throughout the tour, which is organized into 7 sections. The first section sets up the historical figures of the movement: Ingres and Delacroix are surrounded by their disciples and tributes to their vision. Faced with Ingres’ drawings and in particular his studies for the “Grande Odalisque”, Delacroix and Chassériau bring a more real but no less classic vision.

The second section continues this exploration of the human figure, increasingly carried by a real knowledge of the East but always nourished by tradition and fantasy, because, as Eugène Fromentin points out in his book “Un Été dans le Sahara”: “We must look at this people at the distance where we should show ourselves: men up close, women far away; the bedroom and the mosque, never”.

Williamstown, Massachusetts, USA, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute.

From Chassériau (“Moorish Woman Out of the Bath”, 1854, Strasbourg, Museum of Fine Arts) to Gérôme (“Jeune Orientale au Narguilé”, n.d., private collection), knowledge through travel does not obliterate the use of iconographic prototypes borrowed from mythology and classical tradition. The figure of harem, the new Venus, cannot be portrayed in a faithful way, because it remains invisible to all. Gérôme, with his “snake charmer” (c. 1879, Williamstown, The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute) or Édouard Debat-Ponsan (“Le Massage : scène de Hammam”, 1883, Toulouse, Augustin’ Museum), thus renewed a classical and imaginary iconography by presenting it on a background of an Islamic mosaic.

Toulouse, Augustins Museum – © Daniel Martin 8 Henri Matisse

The third section, by Jean-Léon Gérôme (“Le Marchand de couleurs” (Le pileur de couleurs), circa 1890-1891, private collection, on loan to the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston) to Eugène Fromentin (“Le Pays de la Soif”, circa 1869, Paris, Orsay Museum) and Paul Lazerges (“Caravan near Biskra, Algeria”, 1892, Nantes, Museum of Arts) makes it possible to make a transition from the figure to the landscape, by presenting genre scenes that reveal the artists’ simultaneous interest in the figure and its context. This is the beginning of a transformation that leads to an increasing attention to light and the structure of ever purer landscapes.

Between 1820 and 1876 – Oil on canvas – 103 x 143.2 cm Paris, Orsay Museum, legacy Édouard Martell, 1920 Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Orsay Museum) / Hervé Lewandowski

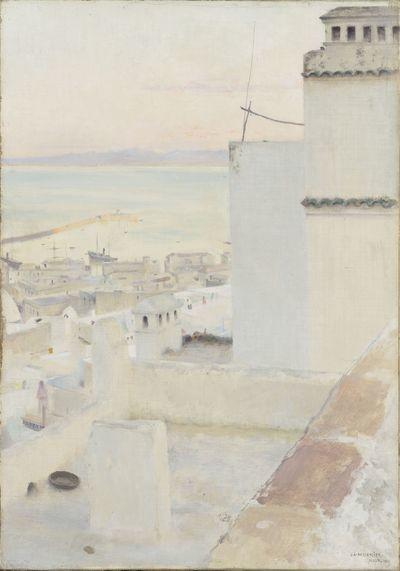

In this perspective, the fourth focuses on this progressive geometrization of the landscape, which reduces narrative data to the essential, concentrates on the composition and rhythm of colours: Jules-Alexis Muenier and Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret, Albert Marquet and Camoin. The geometry and whiteness of the city of Algiers thus inspired Muenier (“Le Port d’Alger”, 1888, Paris, Orsay Museum) to create forms that announced those of Camoin in “Le Golfe de Sidi-bou-Saïd” (1923, private collection) and Marquet in “La Mosquée de Laghouat” (1939, Albi, Toulouse-Lautrec Museum, CNAP deposit).

Faced with this, the fifth section establishes a parenthesis around light and impressionist and neo-impressionist artists: Renoir, with “Le Ravin de la femme sauvage” (1881, Paris, Orsay Museum), paved the way for Théo van Rysselberghe in an essential work on the stain of colour that remained without posterity, but which contributed to the emancipation of colour.

Finally, the sixth and seventh sections, again focusing on the opposition of the figure and the landscape, focus on a radicalization of geometry that coincides with the emergence of new pictorial means. On the one hand, Émile Bernard, Jules Migonney, Albert Marquet and Henri Matisse renew the theme of the human figure by simplifying it. Muslim decorative arts then took on an increasingly important place and made it possible to move into a two-dimensional space. Thus, Bernard’s “Abyssine en robe de soie” (1895, Paris, Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac Museum) or Marquet’s “Intérieur à Sidi-Bou-Saïd” (1923, Le Havre, MuMa) accompany Matisse’s experiments (“Odalisque à la culotte rouge”, 1923-1924, Paris, Orangerie Museum).

On the other hand, Wassily Kandinsky or Paul Klee cross the line of abstraction, linked to the experience of pure colour and glare. This section is an opportunity to rediscover some of Kandinsky’s lesser-known works, such as “Arab City” (1905, Paris, MNAM, Centre Georges Pompidou) or “Oriental” (1909, Munich, Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau), which are gradually changing into pure colour. As Paul Klee notes in his diary during the trip to Kairouan in April 1914: “Color possesses me. There is no need to try to grasp it. She owns me, I know that. This is the meaning of the happy moment: color and I are one. I am a painter.”

Faced with this, Vallotton ends the tour with a tribute to Ingres, “Le Bain turc” (1907, Geneva, Museum of Art and History), strange in its composition as much as in the absence of orientalist motifs. Through the figure or landscape, Orientalism gives way to a radical experience, at the origin of modern art. In both cases, the East disappears to give way to pure painting.

.