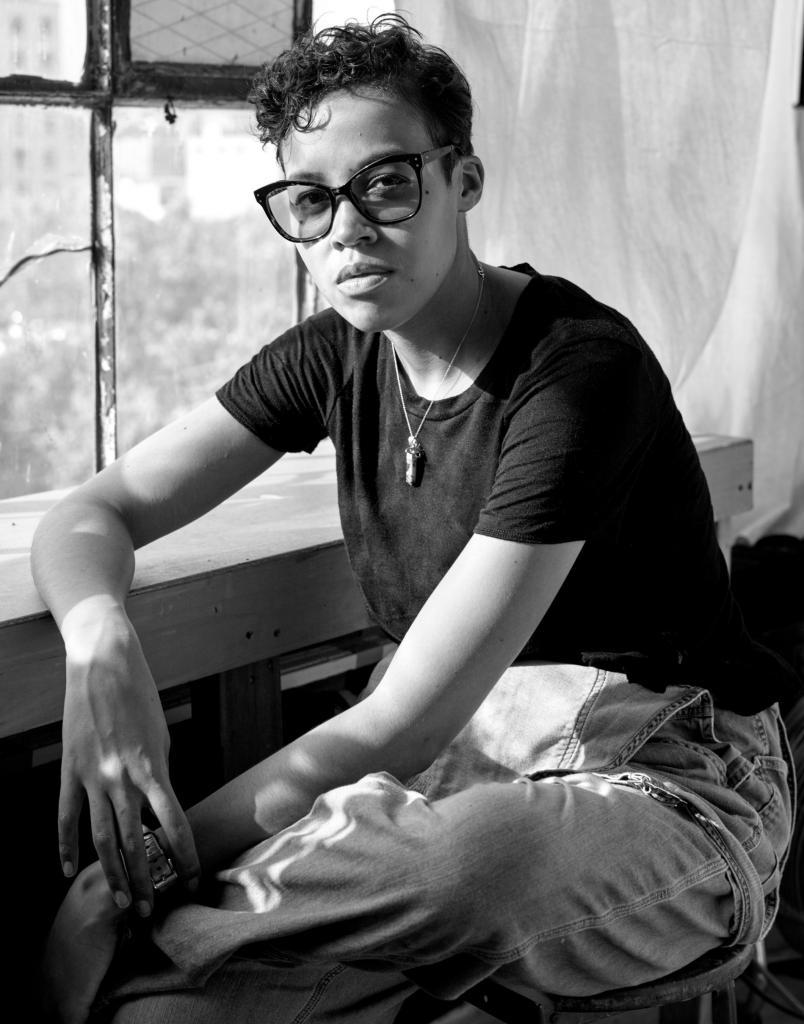

In conversation with Sepideh Mehraban

Sepideh Mehraban reminds us; “It takes years to heal from trauma, but it is not impossible.”

“History and the past are not one and the same.” it is this very simple yet resonant line that makes me pay attention to Sepideh Mehraban’s latest show; Until The Lions Have Their Own Historians, The History Of The Hunt Will Always Glorify The Hunter. The setting off point for this exhibition (which includes eight works of mixed media on found carpets) is, of course, a quote from Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart.

The exhibition proposes to us that history, as a study or retelling of past events, is in fact not neutral—it is shaped, crafted and moulded by those with power, where forces of censorship and propaganda are constantly in operation to undermine and silence.

Mehraban investigates, examines and cross-examines recent Iranian histories using “formal” and “informal” accounts and records (memories, stories, oral history, newspapers, archives, carpets, family photographs); both public and private, real and metaphorical records function as repositories that can be (re)negotiated and (re)interpreted. This amalgamation of personal and public accounts deviates from unchallenged methods that present history as final. Furthermore, the use of abstraction as a mode of creation (with the grid format of the newspaper as a source of inspiration) recontextualises how we think through history, lending the works as prompts into further inquiries as opposed to retellings of ‘facts’.

I interviewed Mehraban to find out more about the exhibition, her research and her practice.

NM: I was intrigued by the notion (in the exhibition text) that history and the past are not the same. Can you speak more about this?

SM: History is only one angle of the past, history is a story we are told, usually by those who manage to speak the loudest. The title of this body of work draws from a famous line in Chinua Achebe’s seminal work Things Fall Apart; Until The Lions Have Their Own Historians, The History Of The Hunt Will Always Glorify The Hunter.

My goal is to challenge the idea that someone or some entity can tell you what happened to you. It’s really critical to have these conversations, especially in places where the conversation is so highly politicised.

NM: Can you speak to us about the format of the newspaper as a source of inspiration? What do you feel this format allows you to do (or not do)?

SM: Newspapers are physical artefacts of the past. They belong to the time when cellphones, the internet and twitter didn’t exist. Their materiality, like books, is nostalgic and also in a way traumatic. They are traumatic because the news is tampered with over the course of history. In the case of the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the news do not follow the narrations and stories that many Iranian families have experienced. The grid of the newspaper is a signifier of the structure of spreading information and at the same time control of information where we see the elements of propaganda and censorship play out. Censorship and propaganda are just as traumatic as the actual violence of revolution.

NM: I’m thinking of the newspaper from the lens of censorship and propaganda (as you’ve mentioned above). Through your explorations of history, what can you tell us about the relationship between these different parts of how history is told and experienced?

SM: My childhood experiences and family’s stories were at odds with the official state history, the controlled and censored domestic news channels, and also with the increasingly reductive international media and its lifeless headlines and statistics.

It is this discord between the grand narrative and the chronicles of everyday people that I explore in my work, the multitude of personal histories behind (and absent from) the headlines and politics. Stories of individual lives, of hopes for change, of disappointment and ultimately of the humanity behind the abstracted media coverage. It’s a subject with universal relevance, as I discovered on relocating to South Africa in 2012. I found parallels between the two countries: the complex histories marked by trauma and political turmoil, empty promises and disillusionment, and the abundant memories and lived histories of ordinary people.

NM: When I think about the carpet and paint over the carpet I have an image of covering and uncovering and I think we can say this with history as well, where we have an understanding of the accounts that make up history until we uncover more and more. With your research into the 1979 revolution, can you speak to us about things that you are uncovering?

SM: The 1979 revolution was a populist and nationalist movement consisting of Marxists, Islamic socialists, secularists and Shi’a Islamists. These diverse groups united to overthrow the monarchy but instead of a democracy, they ushered in an Islamic fundamentalist-led theocracy under Ruhollah Khomeini. There is propaganda by the current government to frame the movement as a religious uprising, which is not the case. The 1979 revolution was an uprising against a dictatorship with a hope for a better future.

NM: Can you talk to us about how you are thinking through post-apartheid South Africa and post-revolutionary Iran, together, if at all?

SM: Both of these countries have complex histories marked by trauma. The recent student movements such as Rhodes Must Fall, Fees Must Fall and Open Stellenbosch of 2015 are indicators of social and political changes. These protests influenced governmental action (e.g. university fees were frozen after the Fees Must Fall campaign in 2015). There were also student uprisings on the other side of the hemisphere in Iran; after the 2009 controlled presidential election, which saw Mahmoud Ahmadinejad come into power. At the present moment, there are still protests occurring in Iran after the increased price of petroleum where people are demanding a long-term resolution from the government. Over the course of a week, the government shut down the internet and at least 106 people were killed during demonstrations. There is no international coverage of this in western media nor in the Iranian national media. People are cut off from the world which is nerve-racking to witness in 2019.

In Iran and South Africa, the student uprisings and protests are characterised by the traumatisation and upheaval of ordinary lives. In both countries, protests are indicative of a need for political change and transformation.

NM: I’m interested in this idea of intergenerational trauma; how do you see this manifesting today and how do we begin to think of ways of fracturing that trauma and moving towards healing?

SM: We need more empathy toward each other and our world. We need more care. We need leaders who promote humanity and equality for everyone. We could make small changes by starting with our families and our communities. We need to listen. There are many voices that need to be heard and it takes years to heal completely but it’s not impossible. The future is bright with our younger generation—with their awareness and knowledge of their world and themselves.

Until The Lions Have Their Own Historians, The History Of The Hunt Will Always Glorify The Hunter is on view at SMITH in Cape Town until 30th November. For more information about the exhibition or the artist, you can contact Jana Terblanche at jana@smithstudio.co.za.