Todd Webb: To read outside the (colonial) frame

Todd Webb in Africa: Outside The Frame is both a book and a survey exhibition about the legacy and work of the American photographer Todd Webb (1905-2000) on the African continent. The exhibition was curated by MIA curator Casey Riley, MIA collaborators, and book co-authors, Aimée Bessire and Erin Hyde Nolan, and is currently presented at the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA) until 13th June 2021.

Presented in 9 chapters, the exhibition showcases over 80 photographs, that Webb took as part of a diplomatic commission from the United Nations (U.N.) in 1958. The photographs were recently discovered by Betsy Evans Hunt, Executive Director of the Todd Webb Archive. The commission by the U.N. was to “document emerging industries and technologies” in the following countries: Ghana, Kenya, Zambia (formerly Northern Rhodesia), Zimbabwe (formerly Southern Rhodesia), Somalia, Sudan, Togo, and Tanzania (both formerly Tanganyika and Zanzibar).

As an initial encounter with the exhibition content and meeting the curatorial team, so many questions came into mind, and are guiding this review: the first one being, why is Webb’s work relevant in the current photographic discourses about the African continent today, when there is an urgent need to focus on underrepresented practices as well as uncovering silenced narratives?

In other words, a key point of reflection was whether we still need outsider views about the continent today in order to analyse, retrospect and make a statement on the violent and “critical period between colonialism and independence”? And who, within arts institutions and museums, holds the right and privilege to define and disseminate this knowledge, for us?

There is also a blurry line about the mission’s intentions – the photographer was commissioned by the U.N., a detail to be analysed carefully in the realm of international operations from the North to the South. Moreover, the commission was never shown, and the negatives disappeared after Webb sold them to a suspicious gallerist and were only recently discovered. Their unuse remains a mystery. One can imagine the propagandist aims of such commission, where African countries would be looked in the North and framed according to levels of “development” and “progress” from a “modern”, Eurocentric gaze and “civilization”.

Leaving the ethical and political questions aside for a moment, the colour photographs are stunning and, in a sense, captured present moments with great style. The privilege of the photographer to be able to be either visible or invisible to its subjects and landscapes is obvious. One can take a closer look and identify his position from photographs to photographs – whether they were an imposed shot or through a genuine encounter isn’t known and revealed but open to subjective interpretations.

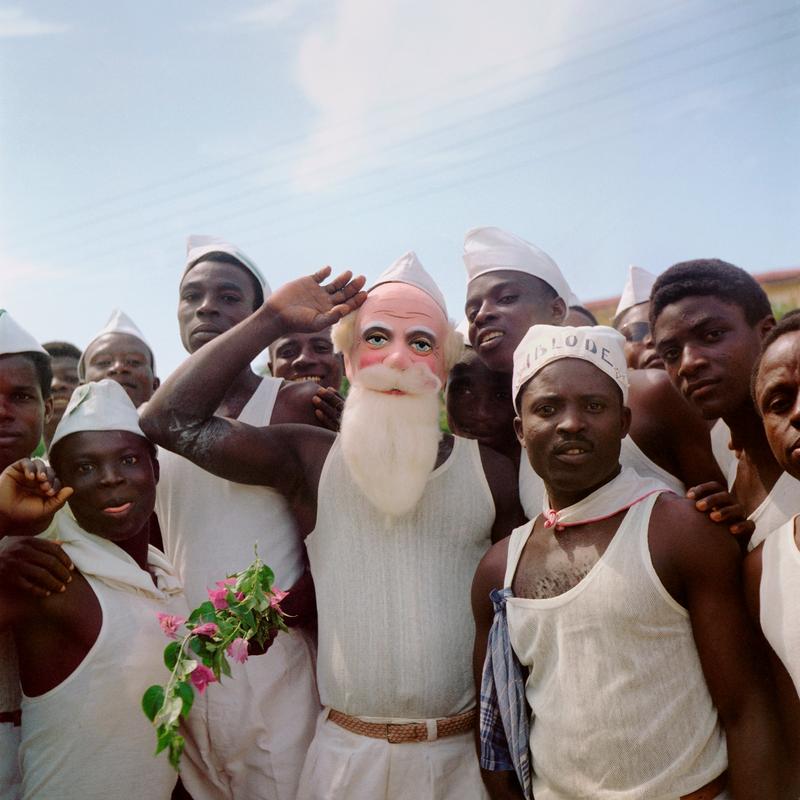

Referring to interpretation texts (Image 1), Webb ‘encountered some difficulty in photographing citizens’ in Somalia (formerly Somaliland), ‘as many were apparently resistant to his requests for posing’, a somewhat revealing statement about Webb’s approach when at work, and contradictory to the curatorial and critical lens that is promoted. Instead, we are faced with a reality of what the medium of photography can be: a tool re-producing violence and breaching ethical boundaries.

The exhibition does not allow for a different or critical reading of his work nor unlock the photographs from the time they were taken. It implicates a certain level of complexity, as well as disparity, about what and who Webb captured in beautiful colour photographs and the reality of the socio-political and economic contexts that he was witnessing.

(Image 2) The photographs are captured with an incredible exposure – creating a harmonious array of colour from the pastel palette to brighter details, such as an individual wearing a very stylish red suit bringing a vibrant energy to the photograph. A photograph for which it is difficult to allocate a specific period of time, or location, and that has a fashion photography energy to it – we almost forget the photograph’s purpose within the diplomatic mission.

By further deconstructing this image, one can imagine either the rapidity of the encounter with Webb, and/or whether it was an intentional shot. The image captured a contextual moment that is revealing of a difference in class amongst the subjects: in the first plan, a working-class worker, in a plough and in the second plan a middle-class man wearing a stylish business suit. Webb attempted to capture a vision of a “civilised Africa” for a Western gaze – Africa as economically thriving, projecting similar entrenched class systems than in the North.

At first sight, the images do not portray a typical romanticized or exoticized version about the continent but allow to seep into an aestheticized idea of what “progress” looks like. Moreover, the exhibition further confuses this paradigm, with, what seems to be a lack of contextual narratives about the historical events at play. It becomes a difficult task for the visitors to deconstruct this photographic language when seeing the photographs.

Visitors will have access to a multitude of similar photographs when navigating (online and on-site) the exhibition’s narratives in a non-chronological flow. The 9 categories include Colonialism+ Independence, Portraits + Power Dynamics and Built Environment, to name a few. Therefore, the journey of Webb’s on the continent classifies the photographs under these broad headlines without the personal stories and counter-narratives that lived in the shadow of the themes. Furthermore, visitors also have access to vitrines in which memorabilia, collected and archived by Webb, are on display, including colonial travel brochures and transport tickets from his journey, as colonial nostalgia.

In spite of demonstrated efforts by the curatorial team, the depoliticization of the context, the inappropriate use of words in the interpretation text (interpretation texts are all available on the MIA website), as well as the broadness of the sections of the exhibition are sadly inscribed within myopic colonial narratives.

According to the words of scholar Tina Campt, visitors should however be encouraged to “listen to images”1Tina Campt, Listening to Images, 2017., question their position, understand and interpret the people and the personal stories behind the images with care and attention, as well as dig into the narratives that is at stake in the background, and somewhat silenced here. There is a need to make a different and independent reading of this photographic material.

How does his work raise critical contemporary questions concerning photography agency, power, racial and national privilege if the resources aren’t offered and the tools aren’t present to allow for a comprehensive and accessible collective reading of the materials and its multi-layered context? It is key to interrogate the place of public engagement around the exhibition that allows a space to uncover important questions. A space that can actively involve people in re-thinking and articulating present and future narratives around the photographs.

In parallel, a book of over 250 pages including photographs and texts, accompanies the curatorial work around the exhibition including contributions from writers, scholars and artists about Todd Webb and this series of work, such as the artist Rehema Chachage and renowned photographer James Barnor. The book was a way to create a collaborative complementary dialogue and share open reflections about the work through formats such as fictional narratives and personal stories, in contrary to an academic voice, or solely by a Western institutional response. Reaching out beyond, the exhibition will be presented at the National Museum of Tanzania and a set will remain in their possession for the creation of new interpretations and narratives on the continent.

However, the broader and local public engagement is neglected which diminishes the intentions that are shared within the statements from the team about unsettling the colonial framework that are deeply rooted within MIA as an arts institution, and this exhibition. When inquiring whether the exhibition will be specifically engaging with a diasporic audience, that live in the city, and relevant to this subject every day led to poor outcomes, and reduced to a few “community conversations”. Bearing in mind that, for example, Minneapolis has one of the largest Somalian population outside of Somalia.

Exhibition-making should be regarded as a statement in creating knowledge with engagement around the questions that it brings to the surface. Arts institutions fail to be held accountable and to work with a commitment to genuinely deconstruct their legacies when shifting the model of the museum to its core, whether from its leadership, the ownership of collections or tokenistic programming practices.

How does Todd Webb’s photographic practice separate itself from ethnographic practices? and in this case, how do we look at his work within the broader “history of photography” in which Eurocentric gaze is prevalent over those that have been systemically silenced and erased from it?

It is a larger exercise of looking at past materials today and having a sincere conversation about the future in imagining the shift that takes us away from violent representations. What is the breadth of interpretation that we’re aiming to create for ourselves and building up counternarratives outside of a neo-colonial frame today?

—

Note: all quotes are from a direct conversation with the curatorial team or exhibition interpretation texts.