In Conversation with Ceramic artist Bisila Noha

Bisila Noha is a London-based ceramicist, whose works draw on different traditional practices of working with clay from around the globe. I talked to Bisila Noha about her process, her influences, and how lockdown has given her an opportunity to reflect on her work and her journey so far.

Could you tell me about how you got started in working with ceramics, and how you became an artist/maker?

I started over 7 years ago when I moved to London. A friend told me, I’m just starting a ceramics course, why don’t you join? So I started doing classes, and I got really into it. Then I went to Italy to do a residency, and I did an apprenticeship in Madrid with a ceramicist, and then I went to Mexico with potters in Oaxaca. It snowballed a bit – when I came back, I had orders and I started doing it full time, basically until lockdown.

It’s been an amazing journey. I don’t think it was a conscious decision, other than to keep learning, but I’m super happy with how everything has evolved and where I’ve arrived. Because I’ve been focused mainly on making functional objects, this year I’ve been trying to see what happens when I am more playful and following my gut feeling.

How important is it for the pieces that you make to be functional, and what made you want to start to be more experimental?

Maybe two years ago or so, I started realising that I was making multi-functional objects. When I started working for myself I realised I’ve been a hyper-productive person, needing to be efficient, which I think is a result of capitalism, and I was projecting all of that into what I was making. Because of the way some pieces turned out, it made them non-functional. That was very hard for me to accept. I just love this, I love how it looks, but it cannot be used. I had to tell myself, let’s embrace this, admire it for what it is. Not everything in life needs to be about being productive.

This year has been another turning point, because I was a bit tired of making tableware, and I had some clay that my parents had brought me from Equatorial Guinea, which is where my dad is from. This is when I started working on the Baney clay project, which is the name of my dad’s village. I realised that’s the way I want to move forward – by having an idea, doing research, having time to think about it, make the pieces, and write about it. It’s a longer process and there are fewer pieces. So I’m enjoying at the moment having time to think, to spend time with the pieces, and coming up with a collection.

It seems like the relationship and connection that you have with Equatorial Guinea has been quite transformative for you, along with your travels to places like Italy and Mexico. All these places have got their own tradition of pottery and ceramics. How have those experiences influenced you?

Massively. I was born and raised in Spain, and I didn’t visit Equatorial Guinea until 2010. I’ve grown up in a very white environment and very detached from my African roots. It’s been more since I’ve been in the UK that I’ve been getting more into discovering that side of me, through Black Feminism, mostly. So having the chance to use the clay to explore all these things, has been amazing.

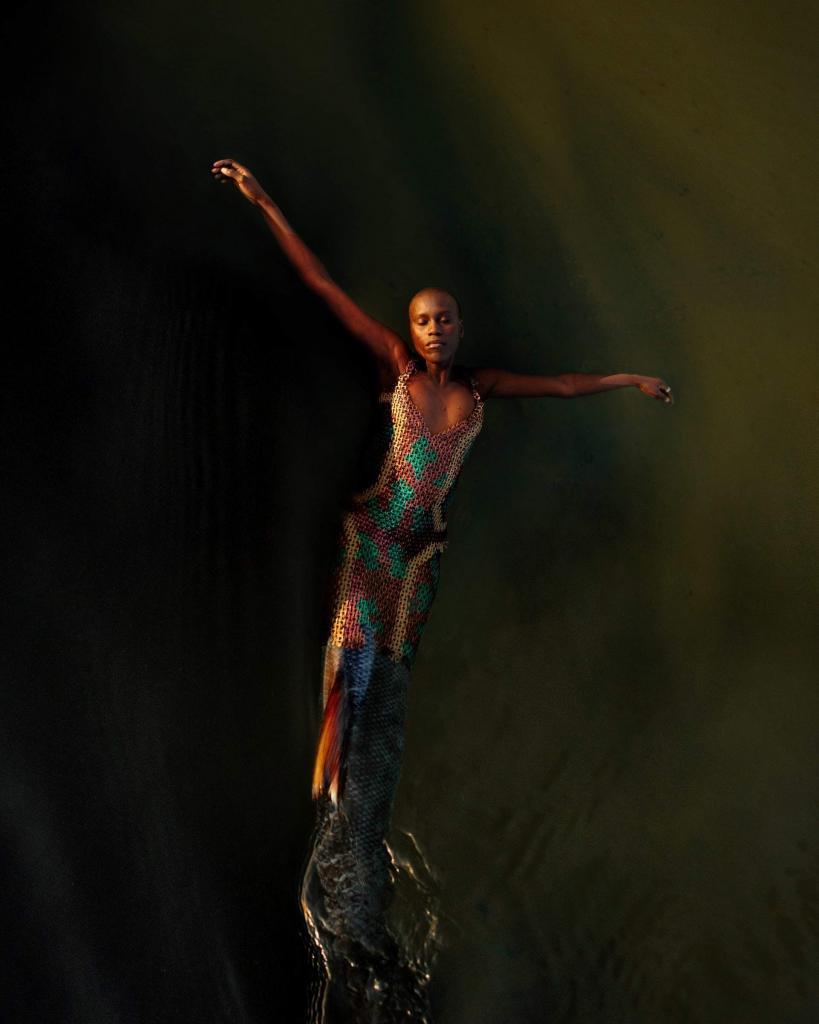

Bisila Noha in Baney village – Equatorial Guinea

The trip to Mexico was very special. In London, and even Italy, you get a bag of clay, you don’t know where it comes from, and then you learn the technique, but I hadn’t learned much about the history of it. When I went to Mexico, I met mostly women who have learned from their mothers, their grandmothers. They go to the mine and they collect the soil, they are one with the clay that they use and the whole process. Clay for them is who they are, and their identity. It also made me realise how long humans have been using clay, and how it can be like a diary of human development and human history. Last year I went to Morocco, and that was something else. It was in the mountains with a woman called Aisha, whose method was so similar to the women in Mexico. It’s so basic, in a way. We are the same people, regardless of where we are, we have the same needs, we tend to come up with the same solutions, and clay is such a beautiful example of this.

What’s the process that you like to use? Has it changed from when you were making the more functional pieces to what you’re doing now?

I’ve mostly thrown – using the wheel – that’s how I was trained. Now I’m mixing throwing and coiling, which is hand-building. I’m thinking of new shapes, I would love to do throwing but changing the shape, like deforming it and finishing with coiling. That’s the direction I want to follow and to keep developing.

Have you found that lockdown has given you more time and more freedom to experiment in that way?

Actually, during lockdown I didn’t go to the studio. I decided to stay at home and write more and try to look at my practice from a distance, so that I can develop the ideas and concepts that I have in my head. It was actually really great to have a break from it, after four years of full-on, being next to the clay every day. Because you make something, and you move on to the next thing and the next thing, and there’s no time to reflect. I think it’s been a process I’ve been in for a while, and lockdown has happened to take place at the same time.

Can you tell me about Gatherers, the exhibition that you were part of?

It brought together artists from different places, who have a special connection with the clay that they use. The exhibition was in Highgate in a place called Omved Gardens, but then lockdown happened, and the gallery that organized this exhibition did an amazing job in creating a virtual experience that was very close to being physical. There is a 360 video so you can move around with your phone and see everything around you. On the website there are also rotating 3D images of the pieces. It created a lot of interest in London, and when they finally opened in July, lots of people went and sales were amazing. But it also gave the chance for people all over the world to see it, which is not something that would usually happen. It was definitely the highlight of my year.

What are some of the things that you’d like to carry forward in your practice?

I am looking at African shapes and trying to replicate them. I’m getting into fertility goddesses, because of the shapes, they are very feminine and connect back to clay being part of the birth of civilisation. So I’m reading, I’m researching and I’m trying to come up with ideas for new pieces. I’ve moved studios and I’m now in a studio with only one wheel so it’s not a place for production – this is the time for me to focus on making whatever I fancy making and grow within that.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. A selection of unique works by Bisila Noha is available to purchase on our website. Click on the link to access it.